Why setting limits as a neurodivergent person is crucial

Disrespectful people, pushy people, abusive people—chances are all of us have at one point in our lives encountered them.

Sometimes we skate by, unharmed. Other times, we’re left with a sour taste in our mouths, bruised feelings, and a sense of injustice.

We may start to think that we’re being actively targeted because of our being autistic and/or ADHD. And the sad truth is we might be entirely correct.

Underdeveloped social skills are a common neurodivergent (ND) trait. Not only does this mean many of us struggle to make and keep friends—but it also means we lose out on the many protections friendship can afford.

NDs may also struggle to understand when someone is or isn’t being their friend. For example, autistics have been found to have a more deliberative (and effortful) thinking style that impacts their ability to rapidly and automatically intuit others’ intentions.1

When we experience bullying and manipulation, we may not only fail to understand what’s going on until it’s too late—we may also struggle to stand up for ourselves.

Often, this is because we suffer from low self-esteem, which is a byproduct of living in an ableist society.

Low self-esteem: a recipe for exploitation

Society constantly sends NDs signals that we are defective, unworthy, and unloveable.

Many of us are criticized for thinking or behaving differently. We’re told we’re are too honest, too blunt, too insensitive, too difficult to follow, too spacey, too weird.

It’s dismissals and criticisms like this that leave us prone to self-doubt and undercuts our ability to be self-reliant.

Thus, when confronted with difficult situations, we second-guess our own feelings and thoughts, spiraling into helplessness. We struggle to find the courage to speak our feelings of pain and anger.

This is because we are fighting two battles. The first is the battle to validate and accept our perceptions of the situation at hand.

When we are taught by NTs that our very frame of reference is invalid, allowing ourselves to believe what we know and feel to be true can conjure guilt, shame, discomfort, and anxiety.

The second battle involves standing up and demanding respect. For NDs, that respect is often denied us. Neurotypicals (NTs) refuse to hear us out, thus creating and reinforcing our negative core belief of unworthiness.

There is also the concern that if we do advocate for ourselves, the other person may retaliate. The penalties can be especially severe if that person occupies a position of power, as is so often the case with bullies, abusers, and manipulators.

There is always the possibility that we will be heard. The person who has aggressed against us may listen and adjust their behavior.

Those who harbor ill intentions may decide that we aren’t worth the effort after all, and move on.

Should we fail to adequately set limits, these toxic individuals will likely linger. And if you’re dealing with someone with a taste for manipulation, they won’t surrender control so easily.

There’s always the possibility they may redouble their efforts, using deflection and personal attacks in the hopes of sapping your resistance.

In these instances, standing up for one’s self can feel possible. But keeping ourselves safe begins with knowing when and how to say “no”.

The seven ‘buttons’ used by bullies, abusers, and manipulators

In Who’s Pulling Your Strings?, Harriet B. Braiker describes seven behavioral “buttons” that difficult people routinely press to pressure and coerce their victims.

It is only by becoming aware of those buttons, Braiker argues, that we can resist manipulators’ control tactics.

1. The disease-to-please: People with this challenge have made their self-worth conditional upon others’ acceptance. Sound familiar?

People-pleasers typically say or do whatever they think is necessary to garner’s approval. How do we beat this habit? By flipping the script.

Start by saying and doing what is authentic and feels right to you.

2. Approval and acceptance addiction: Are you overly nice? It’s common for NDs to overcompensate in order to avoid rejection and abandonment.

Manipulators are known to leverage this fear, withdrawing approval and acceptance to force you into complying with their demands.

If this happens, roll with it. You can’t control whether or not someone decides to write your name in their “good books”.

3. Fear of negative emotions: As an ND, you may often experience anger and sadness and yet deny yourself full expression, so as to de-escalate, avoid conflict, and protect other people’s feelings.

But expressing negative emotions in many cases is justified. If someone punches you in the arm, you have a right to cry out in pain and anger.

You also have a right to tell them how they’ve hurt you and to demand an apology or restitution. If you don’t make it clear to the other person that their behavior is unacceptable, if you don’t clarify your expectations regarding their behavior going forward, it’ll likely continue.

Avoiding and burying your negative emotions means the limit won’t be set, and you’ll be left wide open to a second attack.

4. Lack of assertiveness: People-pleasing as I’ve noted can be a common trait among ND folks, and one often preyed upon by manipulative individuals.

If this is something you struggle with, flex your assertiveness muscles. State your needs and make clear requests. Make it a daily practice. Little by little, you’ll learn to stand up for yourself.

5. The vanishing self: ND folks may have an unclear sense of identity and core values. This is because everything they are and believe in is assaulted by ableist society and NTs on an almost daily basis.

Ableist society wants us to believe that our opinions don’t count and that invisibility is the only way we’ll ever be accepted.

We can start to push back on this by self-advocating. Prioritize your own needs and desires before a manipulator can convince you to prioritize theirs.

6. Low self-reliance: Ableist society tries to convince NDs that their entire way of being is inherently wrong. It teaches us that the only way to acceptance is through conformity.

This can lead to disorientation and dependency. But so long as we are relying wholly on the input and advice of others, rather than what we ourselves know to be true, we remain vulnerable to manipulation.

Recognize that the only perspective that ultimately matters is your own. The life you choose to design for yourself should not be according to someone else’s specifications. It should be according to your own.

7. External locus of control: Those with an external locus of control believe that forces outside of themselves are ultimately responsible for determining the course of their lives.

No surprise that many of us should feel this way, given how what is and isn’t acceptable is so often determined by NTs.

By reclaiming the right to decide for ourselves, we can recenter the locus of control within our own hearts and minds.

From low self-esteem to high self-esteem

Bullies, abusers, and manipulators as I’ve already discussed love to take advantage of folks with low self-esteem, which their victims in turn take as confirmation that they deserve this kind of treatment.

Self-esteem, you could say, is in some ways relational. Others can either damage it, or they can assist with its repair. Seeking a trusting, supportive relationship with a therapist or loved one is one way we can heal our sense of self-worth.

Regardless, the task of pushing back against manipulators will ultimately fall to us. Confrontation, however frightening, is sometimes necessary. And sometimes, it may be as simple as making explicit requests.

“I” statements are helpful here. For example, “I feel disrespected when you name-call. I’m asking that this behavior stop.”

Remember, you have a right to make reasonable requests and for them to be acknowledged. You are under no terms required to explain or defend yourself.

What you want when confronting a manipulator is a commitment to change. Make it a win-win proposition: “Respect me, and our interaction/relationship can continue.”

If, however, the other person won’t accept an outcome short of win-lose, lose-win, or lose-lose, be prepared to pivot.

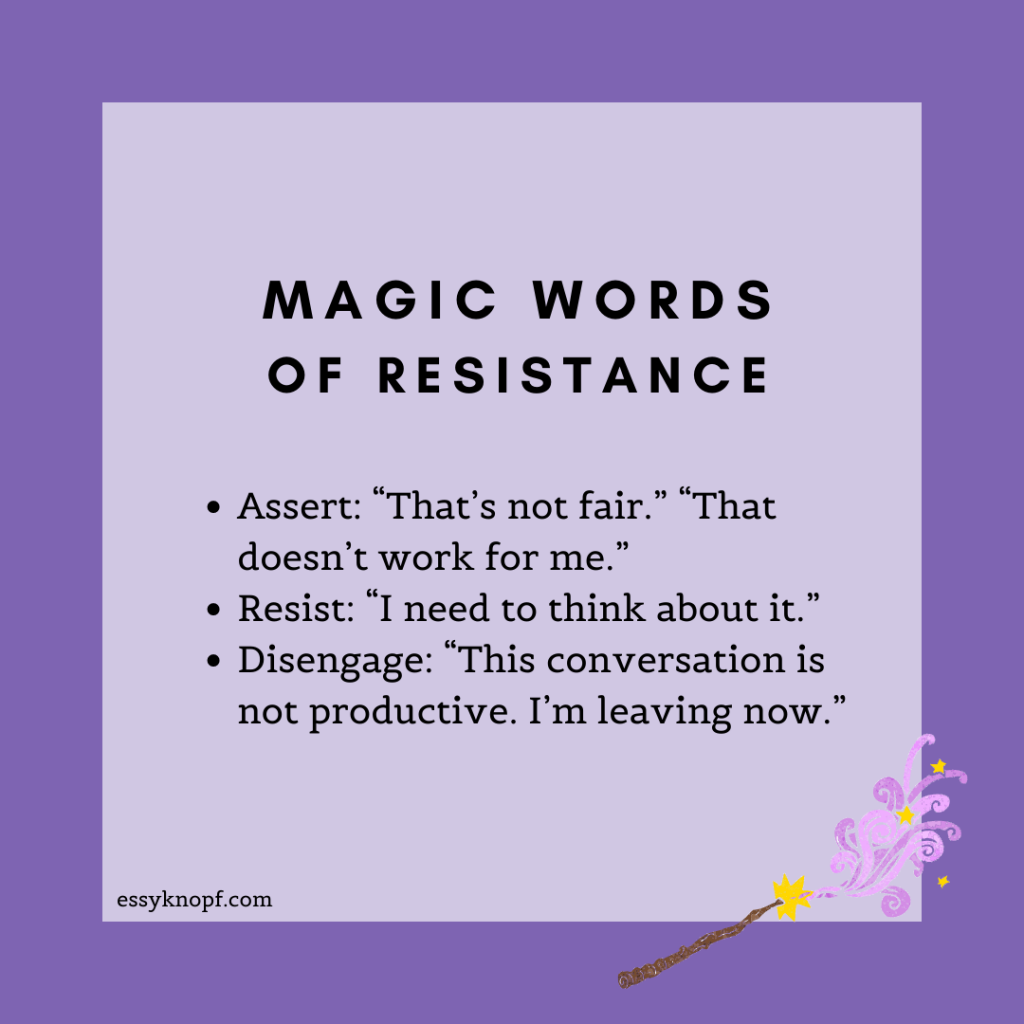

Try these magic phrases

Some aggressors respond to feeling threatened by double-downing or escalating. This may take the form of deflecting, projecting, shaming, verbal abuse, and overly dramatic reactions.

Know these individuals may try to confuse the issue, gaslight you by playing the victim, and/or evade any responsibility. Many even feed off conflict, and anything you say or do that plays into this will count as a win in their books.

Be sure to name any attacks on your person the instant they happen. Send a clear message to the aggressor that you won’t stand for this treatment.

Hold fast to your conviction that no harm has been done by your speaking up. Your goal here is to protect yourself, not the manipulator’s feelings—which probably weren’t in jeopardy to begin with.

Do not be drawn into a point-for-point debate. Instead, assert yourself by saying: “That doesn’t work for me.” “That’s not fair.”

Resist any attempts by the manipulator to wrangle for control by delaying your response by asking for time. For example, “I need to think about it.”

If they try to force an argument, disengage: “This conversation is not productive. I’m leaving now.”

If you’re feeling thrown off balance by the manipulators’ tactics, it’s okay to break off the exchange completely. Tell them: “Actually now is not a good time.” A straight “no” will even suffice, followed by your departure.

And it’s perfectly acceptable to shut down the lines of communication until the other person agrees to follow rules of common courtesy.

If you’d like to try out some of these lines but are worried you might fumble the delivery, practice them by yourself or roleplay with a friend until you feel 100% comfortable saying them on cue.

Reappraising low self-esteem

These kinds of situations and encounters can inflame existing feelings of low self-worth. Address this head-on by checking in with yourself immediately afterward.

How are you feeling about what just went down? Were you fair in your conduct? Did you really behave unjustly, as the manipulator would have you believe?

Imagine for a moment it was your friend making the same request you just made. Would you have listened to them? Would you have been open to change? If your answer is “yes”, then it’s reasonable to assume that it was a fair request.

The bully may accuse you of being equally at fault, but what they are probably trying to do is shift the blame. Refuse to take on any of their accusations.

Also, consider conducting an inventory of your alleged character flaws and using humor to inflate them. Have you, for example, failed to be perfect enough? Are you insufficiently conscientious? Are you an extremely poor people-pleaser?

Now try to name some appropriate punishments for these crimes. If the ridiculousness of it all doesn’t stop you in your tracks, then take it as proof that it is you—above all—who deserves the break.

If these encounters leave you feeling stressed, consider practicing some of these self-care techniques, specifically devised for ND folks.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.