Why pretending to be ‘normal’ leaves us feeling lost

Who are you when you’re under pressure? When you’re in a room where your words are measured, your tone is policed, your very presence feels too loud or too weird or too much?

For many neurodivergents, we learn early that who we are isn’t always welcome. So we adapt. We camouflage. We create a version of ourselves designed to blend in.

Maybe you became the quiet one, the agreeable one, the overachiever. Maybe you tried to be invisible… or, just as often, indispensable.

This is the beginning of the false self: a carefully constructed identity built not from joy or authenticity, but from necessity. It starts as protection. But eventually, the performance gets so convincing, even we begin to believe it’s who we are.

And then, quietly, something even deeper happens: we lose trust in our real self. We wonder why connection feels empty. We stop believing our natural instincts are valid.

That loss is the slow fading of neurodivergent self-worth; a disconnect so normalized we often don’t even know it’s happening.

The Birth of the False Self

Psychologist Carl Rogers spoke of the “false self” as a protective persona; something we construct when the real us feels unacceptable.

For neurodivergents, this construction often begins young, as the result of subtle, consistent signals that tell us: You don’t quite fit here.

Maybe you were the kid who was told to “stop being so dramatic” when you cried. Or you were scolded for flapping, rocking, or bouncing your legs.

Maybe adults praised your “maturity” when really, you were just dissociating. Or you were the student who got labeled a problem for asking “too many questions” or “talking too much about bugs.”

None of those moments feel like major traumas at the time, but they add up. Over time, the message becomes clear: You can stay, but only if you perform. You can belong—but not like that.

So we begin to mold ourselves. We tone it down. We rehearse our facial expressions. We memorize the “right” answers, the “right” responses.

We laugh when we’re confused, smile when we’re overwhelmed, and apologize just for existing too loudly.

Eventually, the line between the real us and the performed version begins to blur. And the more we hide, the harder it becomes to believe there’s anything worthwhile underneath the mask.

This is when our neurodivergent self-worth begins to fracture, and we start to abandon authenticity.

Trauma in a Thousand Cuts

When most people hear the word “trauma,” they picture something catastrophic: a car accident, a natural disaster, a violent event. But for many neurodivergent folks, trauma arrives slowly, in pieces.

It shows up in eyerolls when you share your special interest. In teachers who tell you to “use your words” when you’re frozen in shutdown. In group projects where no one listens to your ideas. In friendships that end the moment you stop masking.

This is complex PTSD, or C-PTSD: a type of trauma that develops from the accumulation of chronic invalidation, shame, and exclusion. The gradual erosion of safety.

Eventually, the world starts to feel like an unsafe place. So our nervous system adapts. We live in survival mode:

- Flight from conversations that feel too intimate

- Freeze when we’re put on the spot

- Fawn when someone seems disappointed in us

- Fight with ourselves, internally, when we “mess up” being neurotypical

In this state, it becomes hard to tell what’s us and what’s fear. And instead of asking, “Why was I treated this way?”, we start asking, “What’s wrong with me?”

This is one of the most devastating impacts of C-PTSD: the way it warps our self-image. The way it disconnects us from our value. The way it convinces us that our neurodivergent self-worth is conditional; that we are only lovable when we are hidden, quiet, or small.

Internalized Ableism: The Enemy Within

Ableism isn’t always loud. It doesn’t always look like bullying or name-calling. Sometimes, it slips into our lives disguised as “feedback,” “concern,” or “normal expectations.”

“Don’t be so sensitive.” “You really should know that by now.” “Everyone else manages. Why can’t you?” “You’re overreacting again.” “It’s not that hard.”

We hear these words enough times, from enough people, and eventually… we internalize them.

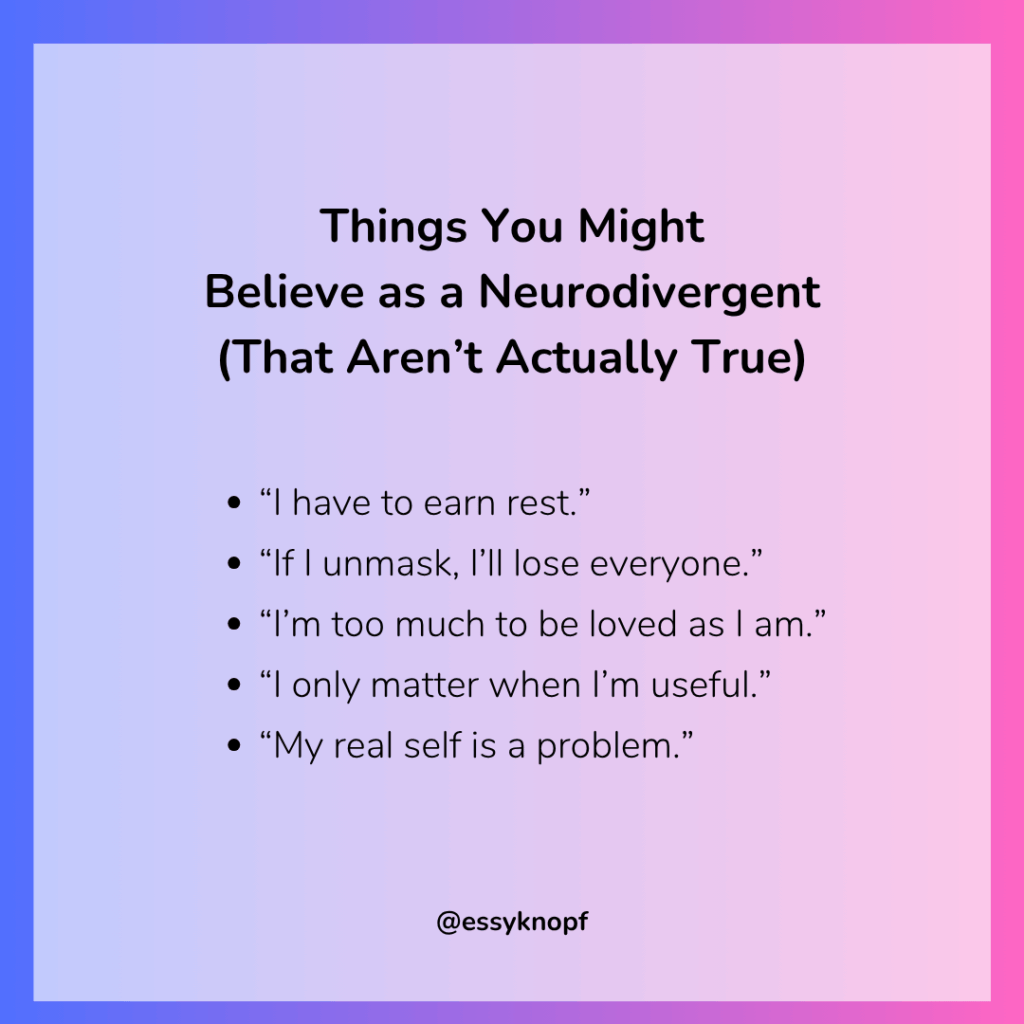

That’s internalized ableism: the process by which we absorb society’s discomfort with our differences and turn it inward. It becomes a private narrative. A rulebook written in shame.

We monitor our own body language. We question whether we’re allowed to say no. We convince ourselves our needs are unreasonable or childish. We treat our natural responses as something to suppress, sanitize, or apologize for.

And the more we self-police, the more disconnected we become from our true feelings. Our intuition. Our limits. We override what our body and brain are trying to tell us, because somewhere along the line, we started believing that our way of being is wrong.

And with every suppressed need, every censored impulse, every moment we say “I’m fine” when we’re not… our neurodivergent self-worth takes another hit.

We find ourselves no longer sure which parts of ourselves are real, and which parts were sculpted to be accepted.

But here’s what matters: That voice in your head? It didn’t start with you. You didn’t invent these criticisms, but you did inherit them.

And you have permission to start questioning them now.

The Voice of the Inner Critic

It shows up just before we speak in a meeting, whispering, “Don’t say that—you’ll sound weird.”

It chimes in after a social interaction: “You talked too much. You made it awkward. They’re probably annoyed.”

It panics when we set a boundary: “You’re being difficult. They’ll leave you.”

That voice—that critical, anxious, rule-obsessed voice—is the inner critic. And for many neurodivergent people, it’s a constant companion.

It might sound like a parent who didn’t understand you. A teacher who was quick to shame. Peers who laughed when you flapped your hands, stimmed, or spaced out. A boss who said you weren’t a “culture fit.” Or a therapist who said, “You can’t be autistic—you make eye contact.”

Over time, those voices blur together. They become internalized, replaying again and again until they sound like our own thoughts.

But here’s what’s important: that voice didn’t come from nowhere. It was learned. Conditioned. Built from repetition. It’s your survival instinct, shaped by rejection.

The inner critic is afraid of being too visible. Afraid of being vulnerable. Afraid of the hurt that once followed your authenticity.

So it tries to protect you. But in doing so, it reinforces the very mask that’s keeping you disconnected.

The first step in softening the critic is to recognize it. To notice when it shows up. To name it. To say: “I see you. I know why you’re here. But I’m not in danger anymore.”

This is a powerful turning point.

Each time we respond with compassion instead of compliance, the critic loses just a little bit of power. And in that softening, there’s room for something else to grow: the voice of self-trust. Self-kindness.

This is the foundation of neurodivergent self-worth.

Grieving the Cost of Disconnection

The journey back to yourself isn’t always filled with joy. Sometimes, it begins with heartbreak.

Because once you start unmasking—once you begin to peel back the layers of who you had to become to survive—you start to see what it cost you.

You grieve the friendships that were built on performance, not presence. You grieve the creativity you shut down just to be taken seriously. You grieve the younger version of yourself who learned to apologize for existing. You grieve the time—years, sometimes decades—spent being “easy,” “pleasant,” “productive”… instead of being real.

This grief is sacred. It means you’re finally noticing the places where you abandoned yourself in the name of belonging. It means your nervous system is starting to feel safe enough to remember what it once had to forget.

And this remembering? It’s messy. It’s tender. But it’s necessary.

Reclaiming your neurodivergent self-worth is about uncovering what’s been there all along, buried beneath layers of compliance and performance.

It’s realizing that you were never the problem. That the way you move, feel, think, and love was never broken… just misunderstood.

And maybe, for the first time, you start to believe that safety isn’t something one has to earn through self-erasure, but something we build by accepting ourselves exactly as we are.

Final Thoughts

Being neurodivergent does not mean we are inherently defective, but rather that we were born into a world that wasn’t built to understand our kind of brilliance.

And so, like so many neurodivergents, we adapt. We craft a false self: an incredible, intelligent strategy designed to protect ourselves. We learned to read the room to make ourselves smaller, softer, easier to handle.

And that strategy worked. It helped us survive. But survival is not the same as wholeness.

And now—maybe for the first time—you’re allowed to want more. Not just peace, but presence. Not just acceptance, but connection. Not just coping, but clarity.

Not just survival, but self-worth: authentic, unconditional, neurodivergent self-worth.

Will you wake up tomorrow unmasked, healed, and free? No. Healing doesn’t work like that. But you might pause before apologizing for something you didn’t do.

You might speak a truth instead of swallowing it.

You might hear the inner critic and choose to answer with kindness instead of obedience.

And with each act of truth, you take a step closer to yourself. Toward the recognition that you don’t need to disappear to be loved. That you don’t need to perform to be worthy.

That you were never too much. You were always enough. Exactly as you are.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.

© 2026 Ehsan "Essy" Knopf. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institutions or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in professional or personal capacity, unless explicitly stated. All content found on the EssyKnopf.com website and affiliated social media accounts were created for informational purposes only and should not be treated as a substitute for the advice of qualified medical or mental health professionals. Always follow the advice of your designated provider.