Yes, male privilege exists. But it carries a terrible cost—especially if you’re gay.

The dominance of the male gender is visible not only in male privilege,1 but also their overrepresentation in high-income brackets and their managerial roles.

It would be easy to assume that the many advantages enjoyed by males serve as a buffer against poorer health outcomes, and yet this isn’t always the case.

Men are for example more likely than women to die early from a number of causes, including suicide.2 This trend is not exclusive to the US but it is present globally as well.

And these early deaths aren’t so much the result of lifestyle choices, some argue, as they are the profound loneliness lingering just below the surface.

The connection between male privilege and loneliness

In I Don’t Want to Talk About It, Terrence Real makes a compelling case for socialization’s role in contributing to the all-too-common experience of loneliness among older men.

He notes that boys compared to girls are typically less spoken to, comforted, and nurtured by their caregivers, leaving them prone to passive trauma, for example in the form of neglect.

Real notes they are also socialized to cut themselves off from their own feelings, their mothers, and from social support.

That is, socialization teaches boys and men that entry to the club of masculinity is dependent upon their continued spurning of “dependency, expressiveness, and affiliation”.

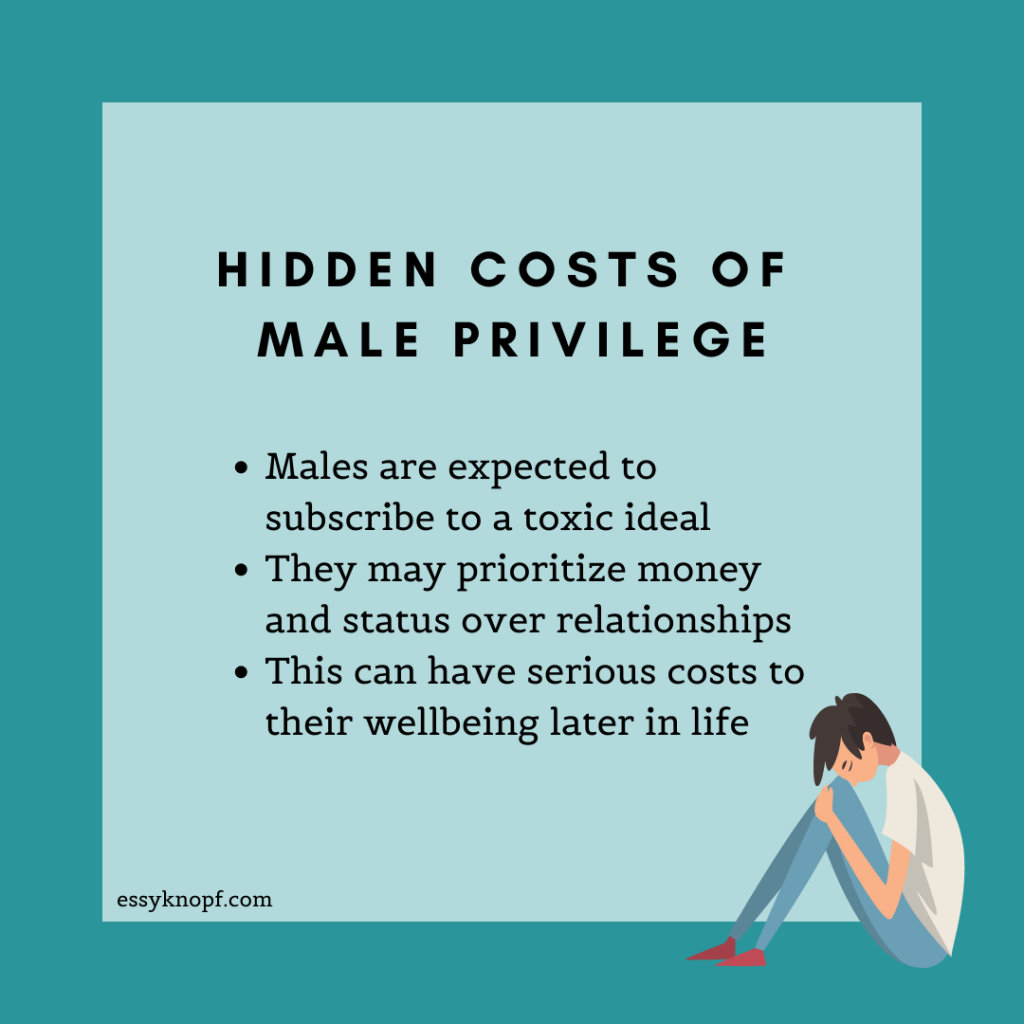

Males are asked to uphold an impossible gender norm closely tied to the notion of rugged individualism.

Real says the cost of passive trauma and disconnection from self and others is that males suffer an unstable sense of self-esteem—and even shame—over their own emotions.

Forbidden the right of vulnerability, males have no choice but to emotionally numb themselves, internalizing rather than externalizing their distress. The result is covert depression.

Having been trained to avoid others’ support, men inevitably turn to “defensive compensations” for this depression, such as drinking, gambling, or sex.

The difficulty, however, lies in the fact that the resulting “addictions do to shame what saltwater does to thirst”.

Similarly, men may also seek an escape through grandiosity, or what Real calls the “illusion of dominance”.

The terrible loneliness of being at the top

What Terrence Real calls grandiosity, Lonely at the Top author Thomas Joiner describes as a fixation on earning money and building status.

Men in their 20s and 30s, he argues, are usually more self-focused than women. They assume an “either/or attitude toward wealth and status on the one hand and social connection on the other hand”.

But as men age, this attitude wreaks a terrible price in loneliness, resulting in significant health disparities and higher mortality rates.

Joiner however diverges from Real’s thesis here by describing factors other than socialization as contributing to the male inability to form and maintain interpersonal connections later in life.

For example, he cites the “people versus things” gender dichotomy. Namely that from a very young age, boys are more interested in things, while girls are more interested in people.

Males are by nature more inclined towards an instrumentality mindset, grounded in “assertiveness, self-confidence, competitiveness, and aggression”.

This is opposed to the typically female, people-oriented mindset, which celebrates expressive traits such as “affection, cooperation, and flexibility”.

Joiner notes other differences, such as the fact that boys get less social coaching from each other and from men when compared to their female counterparts.

Girls also have more gender- and age-diverse friendship networks. This contributes to females as a group enjoying greater interpersonal hardiness.

Having been spoiled with the “institutionalized, ready-made friendships of childhood”, men may fail to develop an appreciation for the “worked-for friendships of adulthood”.

Joiner claims that an instrumentality mindset can also lead to males developing a “don’t tread on me” attitude, best described as a “dogged self-sufficiency in the absence of healthy interdependence”. The links again to rugged individualism are, again, clear.

Joiner adds that “don’t tread on me” carries the tacit message of “don’t connect with me”. As argued by Real, men believe this attitude is necessary to preserving their conferred status as males.

“Don’t tread on me” combined with the single-minded pursuit of money and status normalized by our materialist culture can result in a more passive approach towards relationships.

Men as a result may be less likely to undertake the work necessary to maintain them.

In failing to feed or renew relationships, or to seek out new ones as they age, men may be setting themselves up for significant loneliness down the road.

The fact that men’s internal’s sensors are not fully attuned to their own emotional or social loneliness, Joiner agrees, further compels them to pursue said compensations. And rather than resolving loneliness, they only have the effect of compounding.

The health impact of engaging in addictive behaviors aside, loneliness itself can contribute to poorer health outcomes in later life while corroding one’s resilience and ability to cope with failures, disappointments, and losses.

When compared to seeking professional mental health, compensations are a more likely outcome among males, given that doing the former can threaten the male image of self-sufficiency.

And let’s not forget the stigma associated with male loneliness and accessing such services, which serve as obstacles in their own right.

How intersectionality can deepen male loneliness

Intersectionality argues that it is possible to simultaneously enjoy power and/or privilege in one situation, arena, or aspect of life, and oppression and/or disadvantage in others.

So while being male broadly conveys power and privilege, being an older male in Western society can have serious implications for one’s health and wellbeing.

If one happens to be an older male and have a minority identity such as “homosexual”, the impact can be exacerbated, for example through minority stress caused by stigmatization, discrimination, and prejudice.

This impact grows when one is also a person of color, a trait which brings many disadvantages in a White-dominated culture such as North America.3 4

The minority status of being gay male alone contributes to arguably higher levels of loneliness. And there is also the fact that gay men as a population have to work harder to gain entry to the “male club”.

Hostile attitudes towards homosexuals are often grounded in perceptions of their abnormality, i.e. “Too feminine”.

According to author Simon LeVay, gay men as a population are indeed different, exhibiting a “patchwork of gendered traits—some indistinguishable from those of same-sex peers, some shifted part way [sic] toward the other sex, and others typical of the other sex”.

In Gay, Straight, and the Reason Why, he cites studies that indicate that where it comes to instrumentality and expressiveness—typically male-favoring and female-favoring traits, respectively—gay men tend to be shifted towards the opposite sex.

Having gender-shifted traits in a culture that defines masculinity by limited expressiveness can thus double the pressure felt by gay men to conform to the stereotype.

It also means they are more likely to experience the disapproval of, and rejection by, others who subscribe to the standard (toxic) definitions of masculinity.

Social hostility can generate internalized homophobia, feeding into higher-than-standard rates of depression and anxiety.

It also provides a rationale for the all-too-common flight by gay men into compensations. (Consider here the higher rates of substance use and abuse, out-of-control sexual behaviors, and other process addictions.)

The link between gay loneliness and the potential for harm for example has been demonstrated in a study linking riskier sexual behavior as an avoidance strategy.

Those who engage in this strategy are for example exposed to higher rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

The solutions to male privilege disconnection

To summarize, masculinity is coded in Western society in ways that are emotionally oppressive to males, hence the term “toxic masculinity”.

This oppression is intensified especially the case if you also share minority identities, such as being gay and a person of color.

When combined with a biological inclination towards instrumentality and a cultural bias towards rugged individualism, this can wreak great harm to our mental wellbeing and our relational world.

From this comes disproportionately adverse health outcomes, which as mentioned run in the face of the perceived advantages of being a member of an empowered and privileged gender.

Unfortunately, gender coding and social conditioning have been in existence for thousands of years. The intricate tapestry of our gendered lives cannot be unpicked overnight.

All the same, there are actions we can take as males to address the hidden costs of our gendered identity.

Namely, we can choose to embrace “dependency, expressiveness, and affiliation”. We can strive for a greater connection with our inner selves, and others.

Such connections can be forged, Joiner says, by engaging in shared rituals that create a sense of belonging, togetherness, or harmony, such as sharing a meal with loved ones.

Here are some other suggestions:

Connecting to nature: As men, we stand to benefit by interacting more regularly with nature.

This experience can reduce loneliness, especially when it provides opportunities to interact with others. For example, through hiking or gardening groups.

Daily phone calls: However awkward as calling people up out of the blue may seem today, relying too heavily on text messages can have some serious downsides.

Instead, Joiner suggests calling one person daily, if only for a few minutes.

Whether you have something pressing to talk about is not important. The goal here is to create connection.

Reunions: Organize a reunion with best friends from one’s younger days can be a great way to renews existing connections.

Given the male tendency to lose touch with friendships as we advance towards middle age, this is essential.

A reunion can also bring many of the benefits associated with indulging nostalgia.

Sleep regularization: None of the above is possible if our sleep schedule is out of sync with those of others.

If this is the case, we should consider shifting our life patterns to promote social interactions.

We can this by maintaining a regular sleep schedule and seeking out opportunities to interact with others, such as through a shared physical activity like a sport.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.