Five alternatives to gay dating apps

During my time using gay dating apps, I’ve had several experiences that left me questioning my continued use.

Rarely do they involve something as dramatic as a blow-up or a betrayal. Rather, they usually are the culmination of a thousand cuts.

Many of the people I have interacted with seem paralyzed by choice, requests for emotional availability, and the possibility of commitment. Those lacking in self-awareness will often resort to sabotaging a possible relationship, if only to avoid decision or perceived danger.

The most common form of sabotage is the mixed message: a man claiming to want one thing while indulging in behaviors that ran counter to it. “Looking for dates”, the dating app bio will read, “but open to everything else”.

Should someone make an earnest attempt at courtship, that same man would sooner skirt complications altogether by embracing the easy and “safer” alternative of casual sex.

I first met Rayan* online during college. Years after our first date, he reemerged on Tinder, enthusiastically requesting we meet again.

While I had enjoyed Rayan’s company the first time, I’d felt that our lifestyles and interests were somewhat out of sync. Still, I figured there was no harm in giving it another shot.

We spent the first few minutes of our second date bringing each other up to speed on how our lives had changed in the intervening years, talking broadly about our dating experiences. Rayan expressed frustration about the difficulty of finding someone willing to take the time to get to know him.

About an hour into our conversation, he invited me back to his place for tea. But when we got there, Rayan’s initially chivalrous interest faltered. “Tea”, as it turned out, was a euphemism.

Feeling uncomfortable, I reiterated my intention to date, then noted it was getting late and that I really needed to get home. A conciliatory Rayan offered to walk me to my bus stop and I agreed.

While stopped at a pedestrian crossing, he raised the subject of arranged marriages. In what I can only guess was an appeal to our shared Middle Eastern heritage, Rayan spoke of relatives who would serve as matchmakers to heterosexual bachelors, and lamented the absence of equivalent services for gay men.

“Sometimes I wish I had an auntie who would find me a man to marry,” Rayan told me.

“I wouldn’t have any say in it. She’d choose and that would be it. We’d just have to make it work.”

Rayan laughed at the wistful impracticality of such an arrangement. Yet it seemed to me that for all his facetiousness, part of him meant what he had said.

Rayan’s desire for the implied simplicity of an arranged marriage was understandable, and yet both of us knew this was not something most gay men would ever realistically settle for. Accustomed to the sea of options offered by gay dating apps, to sacrifice those options for many would represent a considerable loss.

The fact Rayan had floated such an alternative to modern dating while on a date struck me as evidence enough of this. What on the surface it was a throwaway joke, it also felt like an offhanded dismissal of my attempts to get to know him.

Rayan over the span of our encounter had gone from stressing he wanted to date, to propositioning me for sex, to lamenting the difficulties of dating – a series of contradictory actions I suspect most people would struggle to decipher.

Like many men I have dated, Rayan either did not know what he truly really wanted, or feared admitting it and sticking to his guns.

When confronted with the emotional danger of being authentic, Rayan had resorted to humor as a defense mechanism, trying to create distance from that perceived danger.

The problem of gay dating apps

Those of us regularly exposed to the toxic environment of gay dating apps are intimately acquainted with the push-pull of wanting more, but fearing what that might entail.

We know it not only just by our own internal experience, but by the inconsistency of our dates who are hampered by the same contrary desires.

It is true that where it comes to building relationships, gay dating apps pose a number of fundamental challenges.

Previously I’ve noted how these apps can create an unhealthy dependence, asking us to engage in inauthentic behavior, while keeping us locked in a perpetual search and encouraging us to trivialize both ourselves and others.

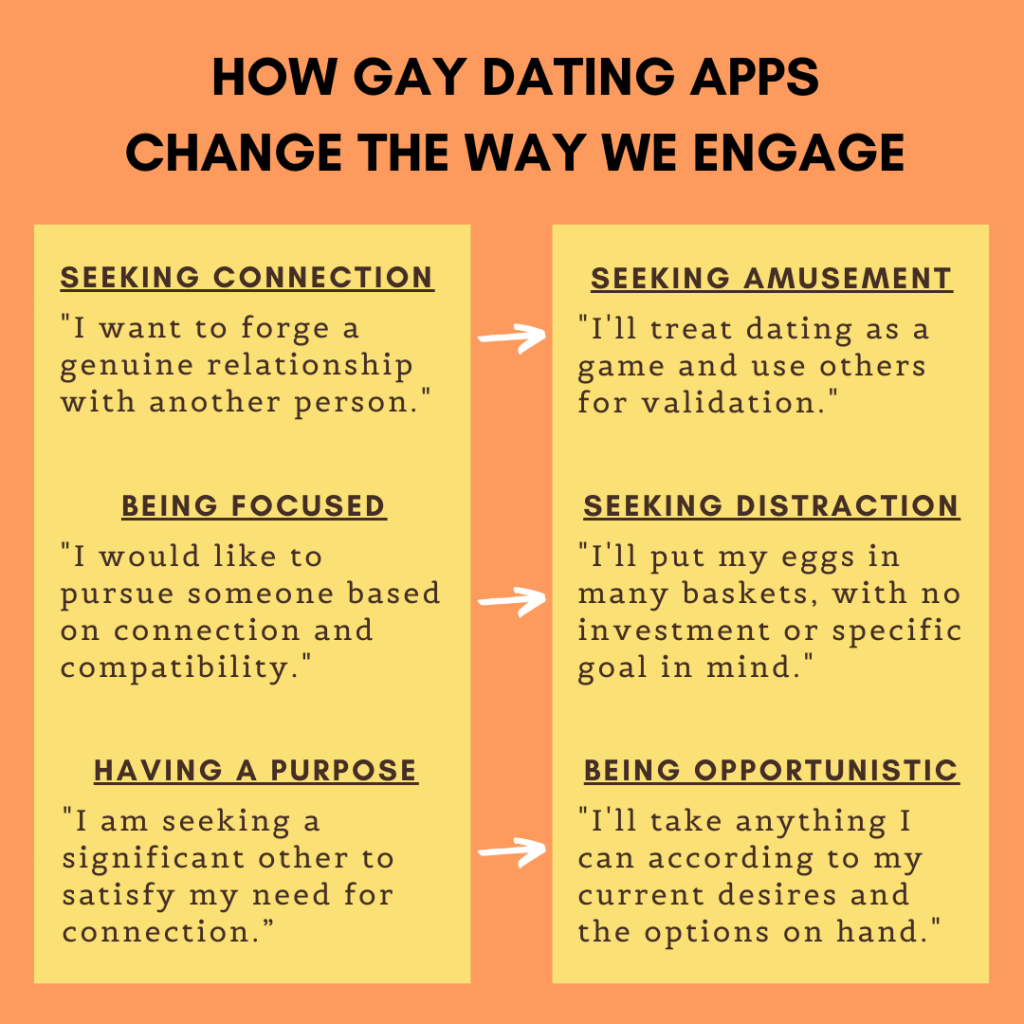

At the heart of the current gay dating app crisis is a fundamental shift in our orientation from seeking connection and being focused and purpose-driven, to seeking entertainment, distraction and being opportunistic.

The gamified reward system used by these apps tempts many of us into adopting such a stance, thus undermining our search for wholesome, meaningful relationships.

The promise that gay dating apps will economize our time and effort may lead us down a downwards spiral of risk aversion, leaving us less willing to take a chance on others, even if all that involves is the price of a coffee and an hour of our time.

The illusion of always being connected offered by text-based communication may also allow us to temporarily stave off loneliness while creating conditions that ironically feed that same isolation.

Text-based communication is also designed with personal convenience in mind, enabling us to effortlessly retouch our self-presentation, while avoiding situations that necessitate vulnerability, which is crucial to forming connections.

The antidote

Not that long ago, dating apps were seen as a somewhat unsavory fringe alternative to traditional dating.

Now, in an uncanny inversion of roles, they have become the new norm, with real-life for many gay men assuming the title of “alternative” – for which we can find any number of excuses.

The bar and club scene? Not quite your jam. A matchmaking service? An unnecessary expense. Gay hobby groups? Too much of a commitment.

But to end our seemingly interminable search for an ideal partner, we must be willing to abandon the ease and comfort of text-based communication and truly invest in others.

In order to forge authentic relationships, we must give up the immediate gratification of texting and allow ourselves to risk vulnerability,

What I am advocating here is not a complete flight from text-based communication. Nor am I suggesting seeking out matchmakers or arranged relationships. Neither promise a true end to the crisis of choice that is modern dating.

What this crisis calls for, rather, is a return to basics. Namely, the crucial art of making and building friendships.

Don’t date. ‘Friend’

Friendship is the foundation of any sound romantic relationship. It does not carry the same emotional risks as gay dating, nor the ambiguity of app-based interactions. It facilitates not a dropping of boundaries and headlong plunge into sexual relations, but the slow and steady building of rapport and trust.

It stands to reason, therefore, that those of us seeking to date should make it our number one priority. We must be willing to shift our outlook from the limited confines of seeking a sex partner or significant other that ticks all the boxes, to the endless horizon of friendships.

How do we form friendships? Former FBI agent Jack Schafer offers the following formula in his book The Like Switch: Friendship = proximity x frequency x duration x intensity (PFDI)

Schafer defines proximity as being close to the subject in question. Frequency is relational to the number of times you’ve been in contact. Duration is the amount of time you spend together. Intensity measures how much you are able to satisfy others’ needs through your actions.

So, what are some settings that are conducive to PFDI?

1. Hobby groups

A hobby group or sporting group is the perfect PFDI nexus. They connect you to a community of like-minded people (proximity), and they give you an excuse to regularly gather with others (frequency, duration) to participate in a shared interest (intensity).

You can find an array of options on Google, Meetup.com, or social media. If you’re feeling particularly intrepid, you could try establishing your own community. Setting up a group on Meetup.com, for example, is easy enough, although it does involve recurring fees.

2. Online communities

Online communities organized around a common interest can also provide regular relationship-building opportunities. This is presuming they are, again, gay-oriented and regularly organize in-person meetups in your town or city.

One possible place to look for these is on Reddit.

3. Meditation or spiritual groups

Shared values are a great basis for connecting with other people.

Whether you are dabbling in mindfulness, practicing yoga, or were raised with a religion that remains near and dear to your heart, chances are you’ll find there is already a gay community that shares your practices and is waiting to embrace you with open arms.

4. Talks, presentations or conferences

Find a talk or attend a conference that aligns with your interests. If it is gay-themed, all the better.

You will stand a better chance of making friends if you attend after-event drinks, networking mixers and bar crawls.

5. Volunteering

If you’re not comfortable putting yourself out there, volunteering – particularly for an LGBT-related cause – is a great way to meet other mindful individuals just like yourself.

Not only will you be doing a valuable service for your local community, but you’ll also be putting your values into practice. This is an incredibly effective way to reinforce your sense of self-worth.

People who are confident in this sense tend to be more attractive to others, thus further improving your chances of meeting someone.

Watch out for the toxic trio

Whatever you choose to do, remember to avoid gatherings that replicate the dynamic of gay dating apps.

Be on the lookout for what I call the toxic trio: objectification, judgmentalism, and competition.

These three things are to friendship what concrete is to grass, suffocating any possibility of growth.

Some sports leagues, for example, can produce an unhealthy atmosphere of competitiveness, in which you may feel compelled to constantly prove your athletic ability and in turn your personal worth. Should you fail to measure up, you may face subtle and even overt forms of exclusion and judgment. Hardly the kind of environment that is conducive to friendship.

Depending on the kind of social gathering, you may get the vibe that other attendees are less focused on connection than they are cruising. A common telltale of this is what I call the “wandering gayze”, in which the person you’re talking to looks over your shoulder, constantly scanning the room for better-looking prospects.

The wandering gayze is the scourge of many an interaction between gay men. It sends a very clear message to one’s conversation partner that their value as a person is pending review.

Besides being a covert form of judgmentalism, the wandering gayze indicates that this person has an agenda, even if that agenda is simply to keep “trading up”. No one should ever feel forced to fight for another person’s attention or respect.

Keep an open mind

Always being on the lookout for the next best thing is counterintuitive to the dating process. Should you find yourself falling prey to the wandering gayze, you should remember that your goal here is to build connections based on mutual interests and camaraderie.

For these to be possible, you should approach these groups and events with an open mind, rather than a specific motive. Of course, your end goal may be a romantic relationship, but being too fixated on the goal closes you off to possibilities.

Strict adherence to a nonnegotiable shopping list is one reason gay dating apps feel so sterile. By remaining open-minded, you will be avoiding squeezing every interaction into a predefined box.

Instead, you are granting yourself permission to freely engage in a sharing of self through conversation, laughter, and flirtation; to let down your guard and be vulnerable. And vulnerability is where the magic ultimately happens.

In joining one of these groups, you may not find a life partner. But you will likely build rich, rewarding friendships that increase the possibility of further introductions.

Remember that you are playing the long game. You are investing in other people in the hopes they will in turn invest in you.

This may feel like a somewhat inefficient, if not risky process. In abandoning the pretense we employ while texting, we may say or do the wrong thing. We will likely face pressures and discomforts we might have otherwise avoided, had we remained behind our phone screen.

What we won’t do, however, is leave these encounters empty-handed. Given the right company, we’ll instead walk away with the warm glow of a fun conversation, a shared joke, or an exchanged smile.

And after so much time spent in the gay dating apps wasteland, in the company of men apt to send conflicting messages, is that so bad?

Takeaways

- Swap gay dating apps for in-person interactions.

- Aim to find friends – not dates.

- Consider attending events or groups that offer proximity, frequency, duration and intensity.

- Embrace vulnerability by remaining open.

* Names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of all individuals discussed in this article.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.