Why childhood autism and ADHD often go overlooked

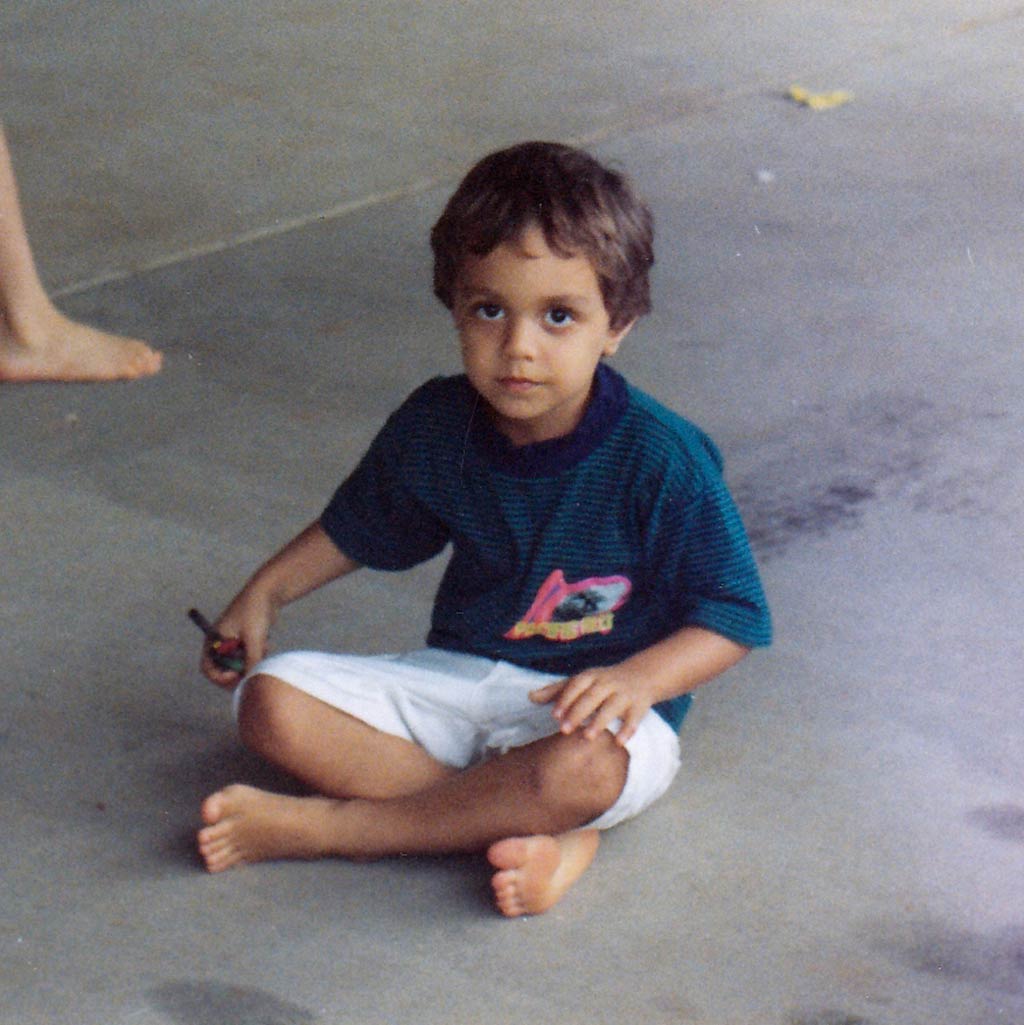

Childhood autism and ADHD aren’t always obvious…except perhaps for the neurodivergent (ND) child themselves, who comes to the realization early on that they’re different.

It usually begins with other kids calling out our behaviors, telling us that we’re weird, or implying we’re inferior.

People clearly found me strange, but in my view, I was just unique and misunderstood. These two words perfectly summarized what it was like being an undiagnosed autistic and ADHDer in an ableist world.

They also describe why I often felt driven to mask my ND traits, and perhaps why many of them went overlooked.

But suppose I hadn’t masked. Suppose I made no attempt to conceal my supposed weirdness. Would I have received a diagnosis and received the necessary support sooner than I actually did?

Possibly—but possibly not. The lack of general awareness and education about autism and ADHD meant my traits would have continued to have been misattributed to my personality or (apparent lack of) intelligence.

This also comes down to the fact that autism and ADHD manifest quite differently for each individual. It thus requires a discerning eye to identify its presence.

Here’s how autism and ADHD showed up in my childhood.

Stimming: a common sign of childhood autism and ADHD

For years after receiving my autism (and later ADHD) diagnosis, I convinced myself that I had never stimmed. It was only upon hearing the accounts of other autistic people that in fact I did.

When I was living in the tropics, my favorite thing to do on a hot day was to chew on ice. Sure, it was refreshing, but the crunchiness of it was also deeply satisfying.

Another thing I loved to do was to play with chewing gum. Countless hours were spent blowing bubbles or pulling long strings of the stuff out of my mouth.

During long car rides, I would beatbox—it was a practice I never seemed to grow tired of.

When I was 12, I also went through a period of sucking obsessively on a certain toy. (By “toy”, I’m referring here to a balloon stuffed with flour, with a pair of googly eyes and a cap of yarn hair.)

It was a kind of sensory ball, and it lasted all of a few weeks before suddenly exploding and spraying flour all over me. Imagine having to explain this development to my parents!

Another big stimming activity for me was delivering a series of DoggoLingo-style monologues to animals, such as the family dog, in a made-up accent.

For days, weeks, months, and even years afterward, I’ve felt the urge to recite DoggoLingo phrases of affection to myself, at random, for no clear reason, over and over again.

This behavior I previously thought was echolalia, though I’ve since learned the correct term for this is palilalia: the delayed repetition of words or phrases.

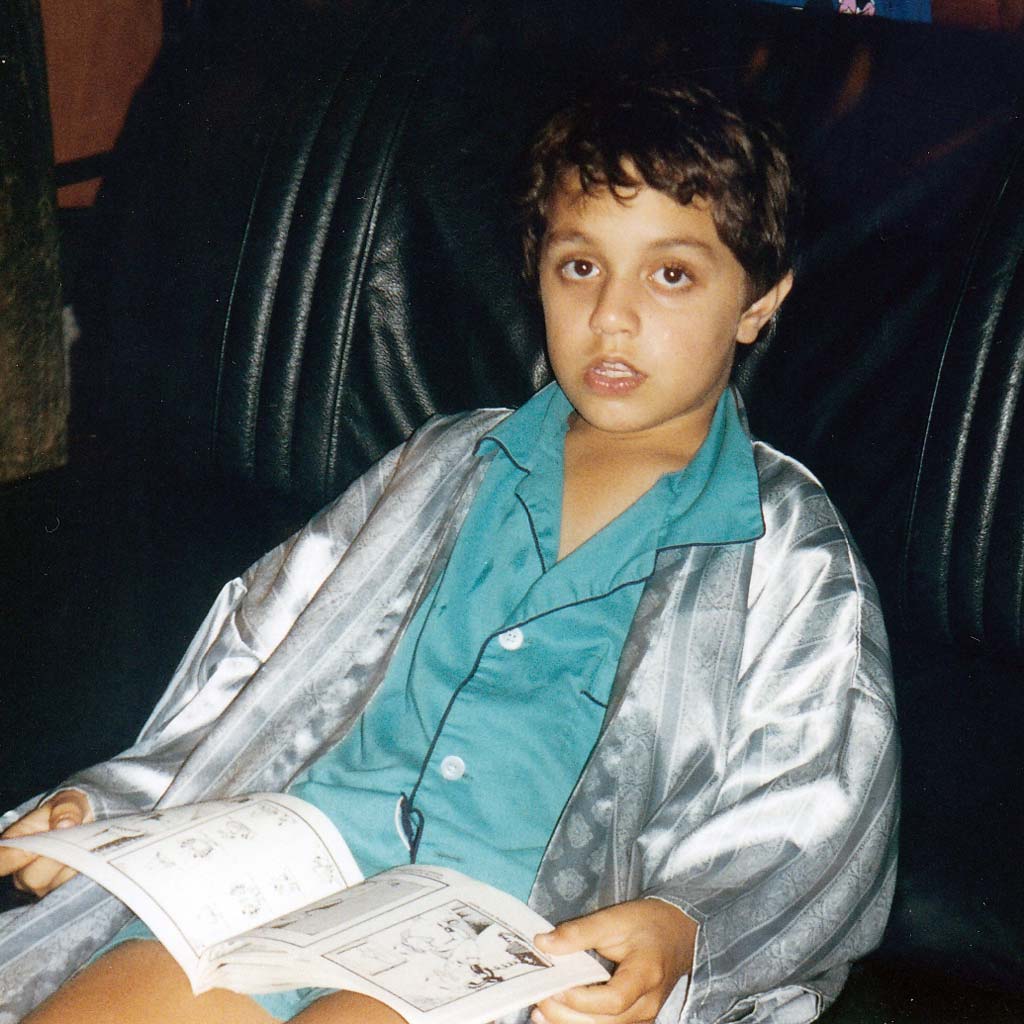

Obsessive interests

My childhood autism/ADHD was perhaps most evident in my obsession with insects and spiders. Collecting factoids about each species proved a source of great delight.

In my teen years, my area of interest shifted to fiction writing. The fantasy worlds I created provided an escape from my confusing and often overwhelming reality.

Where previously I collected bug-related factoids, I started collecting new words, memorizing them straight out of the thesaurus.

There was a certain pleasure to be found in this mastery of meaning. To me, acquiring words represented the acquisition of some kind of secret, important knowledge.

Many of these words had a delicious quality to them. Consider for instance “lignite”. No idea what it means, but pronouncing it aloud just feels satisfying.

More than a decade later, riffling through a box of keepsakes, I would find ratty little lists of words I’d picked out from books, preserved since my teenagehood.

If you asked me to explain why I was keeping them, I’d be at a loss for…well, words. Even now, the very idea of throwing them away evokes pain.

The obsessive collecting didn’t stop there. At one point I received a pocket organizer with a digital address book, which I felt compelled to fill with phone numbers.

Despite the unusualness of my request, many of the people I asked at school obliged me by providing their own. I even worked up enough courage to ask my math teacher—of all people—for her details.

Suffice it to say, my teacher was not all too impressed, and I became the laughingstock of the class.

Social, environmental, and animal rights activism

An interest in environmental and social causes was one trait that’s typical of childhood autism.

I remember being age six and penning a handwritten letter to the Australian prime minister asking him to increase foreign aid to famine-stricken Sudan.

In fifth grade, I used my valuable show-and-tell time to lecture my peers about Captain Planet and climate change. While almost everyone rolled their eyes at me, I of course now have the satisfaction of knowing I was right all along!

My interest in animals also led to me adopting vegetarianism, a phase that lasted all of one year….before my mother tricked me into believing there was no meat in lunch meat.

Fixing things and the problem-solving mindset

When any of my toys broke or stopped working, I worked obsessively to try and fix them.

The most memorable example of this was a special doll that could pee when “fed” milk. At some point, the doll stopped peeing. Concluding that there must be some kind of internal blockage, my six-year-old self decided to clear this blockage using a reed.

Granted, this was not exactly ideal behavior for a would-be future parent, and yet this ability to hyper-fixate—a quality that appears in both ADHDers and autistics—would later prove quite advantageous, especially when it came to problem-solving.

The same probably couldn’t have been said of my tendency to always try and set things right. In second grade, my homeroom teacher one day warned my peers that someone had been stealing food and money from backpacks.

Our school didn’t have lockers. Students instead had to leave their backpacks on racks. Given most of my peers were leaving their bags unzipped, the temptation to would-be thieves naturally was great,

I thought long and hard about what I could do to fix this problem, then spent the following lunch break methodically zipping up every bag I could get my hands on.

I was a self-appointed Good Samaritan, but that wasn’t how two of my classmates saw it. They reported my apparently suspect behavior to the teacher, bringing a sudden end to my brief career as a school crimefighter.

Sensory sensitivities

As a child, I was accused of being a “picky eater”. What the adults around me didn’t understand was that I found certain foods extremely repulsive, usually because of their appearance, texture, taste, or a combination of all three.

One of these foods was yogurt. Another was a traditional Iranian stew my mother would make which contained red kidney beans and lamb shoulder called ghormeh sabzi.

Ghormeh sabzi was one of the few foods I devotedly ate, due to the delicious umami flavors, and yet I was extremely averse to doing so until the beans and lamb had first been removed.

Certain sensations could also make me very uncomfortable. Feeling my toenails against the surface of a pilling bedsheet was one of them. To avoid the possibility of contact, I became a stomach sleeper.

As for sleep, that was an activity that felt next to impossible unless I was under a sheet or blanket. Another requisite was that I needed to have a fan blowing on me—no matter the temperature.

Tags inside my clothes bugged me, and sometimes even my own underwear felt too tight.

One time, a teacher caught me trying to adjust my briefs through my pants and assumed I was having some kind of bladder problem.

Wrap up

As perfectly natural as these preferences and behaviors felt to me, the downside was often obvious and immediate: alienation.

In the eyes of my parents, peers, and teachers, I was either too finicky, too stubborn, too sensitive, too clueless, or too weird. And without a diagnosis, what cause did I have to disbelieve them?

But to view our authentic ND selves in such a light can leave a legacy of shame.

It’s only now, years later, that I realize the problem was less my difference than the ableist system that defined that difference as a problem.

So to all my fellow autistics and ADHDers experiencing self-doubt: don’t shy from authenticity. Embrace it as your fundamental right.

What were your ND traits as a child, and how did others react to them? Let me know in the comments.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.