When rest feels like failure: Understanding neurodivergent dopamine crashes

You make it through the week: meetings, deadlines, errands, everything on your list. You tell yourself, “Just get to Saturday.” And then, it arrives. No alarms. No emails. No obligations. A full day to yourself. Freedom.

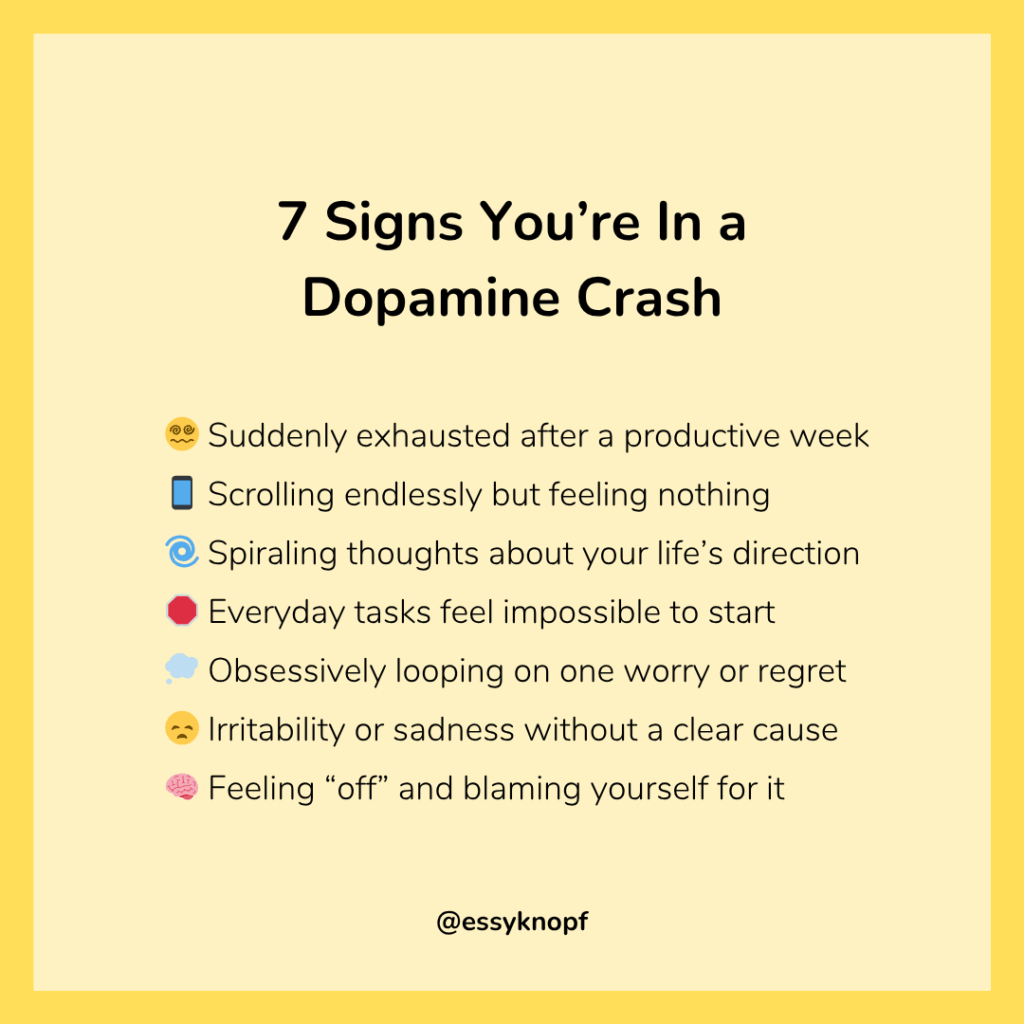

But instead of relief, you feel an invisible weight pressing on your chest. You wander the house without purpose. You open your phone and scroll without focus. You think, This should feel good. Why doesn’t it?

A subtle dread creeps in. You start to feel unmoored, like you’ve slipped out of sync with the world. There’s nothing anchoring you, and instead of feeling free, you feel lost. Tired, even though you slept. Sad, even though nothing’s wrong. Irritable, but without a clear trigger.

This strange shift can feel so personal, like a flaw in your character. But for many neurodivergents, especially ADHDers and autistics, what you’re experiencing isn’t laziness or emotional instability, but rather a dopamine crash: a neurological dip that often follows periods of high stimulation or intense focus.

And when it hits, it sets the stage for something even more destabilizing: The Inventory.

The Inventory: When the Brain Turns Inward (and on You)

The Inventory doesn’t ask for permission. It doesn’t arrive with warning signs or knock gently on the door. It just appears, and suddenly, your brain is running an audit of your entire existence.

You’re lying in bed, or sitting on the couch, maybe halfway through a cup of tea. Then it begins: Am I doing enough with my life? Am I falling behind? Why don’t I feel closer to my friends? When was the last time I felt truly happy?

This is The Inventory. And it rarely pulls punches. It sifts through your relationships, your career, your body, your dreams… everything you’ve ever wanted or failed at. It’s as if your mind is trying to organize emotional clutter with the efficiency of a tax auditor on a deadline.

And sometimes, it hits on truths. Maybe you do want deeper friendships. Maybe your job is unfulfilling. These aren’t imaginary complaints. But what makes The Inventory so overwhelming is when it shows up.

You weren’t feeling this way yesterday. In fact, you might have been laughing, feeling connected, energized, even hopeful. What changed? The stimulation stopped. The dopamine dropped.

And that’s the crucial clue: The Inventory doesn’t start because your life fell apart. It starts because your brain, suddenly low on dopamine, is trying to explain the internal discomfort. It misreads chemistry as crisis. It turns a biological dip into an existential one.

When you understand this, it doesn’t erase the discomfort, but it can disrupt the spiral. Because The Inventory is often a sign that your nervous system is dysregulated and looking for meaning in the silence.

The Real Culprit: Dopamine Dysregulation

To understand what’s happening during these emotional plunges, we need to talk about dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that helps us feel motivated, curious, and emotionally alive. It’s the chemical behind the little spark we feel when we start a project, connect with someone, or even just finish a to-do list.

For neurotypicals, dopamine flows relatively consistently. For many neurodivergent folks, especially autistics and ADHDers, dopamine is… spikier. It’s less like a gentle stream and more like a faucet someone keeps forgetting to turn on.

That means we might feel flat or irritable in the absence of stimulation, and euphoric, engaged, or even hyper-functional when we’re riding a dopamine high. And when that high ends—whether it’s after a project, a social event, or just the daily busyness of life—we crash.

You might feel heavy-limbed, foggy, or like you’re moving through molasses. Your interest in things you normally love evaporates. Your tolerance for noise, mess, or interruption drops to zero.

Because from the outside, nothing’s wrong. No crisis. No tragedy. And yet your body and brain are reacting like you’re in distress.

That’s the nature of dopamine dysregulation. Your brain has the chemicals it needs to feel balanced. And when it doesn’t? It tries to make sense of the imbalance. That’s where The Inventory comes in. It offers explanations—harsh ones—for what is, at its core, a neurological shift.

Recognizing this doesn’t make the crash go away. But it can give it shape. And with shape, you can begin to respond with understanding instead of self-judgment.

Dopamine Farming: How We Cope Without Knowing

When our brains are running low on dopamine, they don’t just sit back and suffer. They hustle. They scavenge. They adapt. This survival mode often leads us to something I call dopamine farming: the unconscious practice of seeking out tiny, fast hits of stimulation to offset the internal crash.

You’ve probably done it without even realizing. Maybe you open five tabs at once, scroll three different apps in rotation, snack even when you’re not hungry, or dive into an hours-long TikTok rabbit hole. This is your attempt to self-regulate.

Some of this is benign. Some of it is even creative, like switching between hobbies, dancing in the kitchen, or watching three episodes of your comfort show in a row. These can be gentle ways of topping up a depleted brain.

But not all dopamine farming is sustainable. For many neurodivergents, especially those with ADHD, the farming can become compulsive. What starts as a coping mechanism can spiral into overstimulation or burnout. You keep clicking, watching, doing, hoping to find the thing that gives you that little “zing.” And when nothing works? The crash hits harder.

The real catch is this: dopamine farming builds tolerance. That new app that gave you joy last week? It’s boring now. That hobby you used to love? You can’t get into it. You need more, faster, louder. And eventually, there’s nothing left to mine.

This is a strategy your brain has developed to stay afloat in a neurotypical world that rarely offers the kind of stimulation and structure you actually need.

And like all survival strategies, it works… until it doesn’t. Recognizing your farming patterns can help you shift from unconscious reaction to intentional support. You don’t need to give up dopamine farming altogether. You just need to diversify your crops.

Mountains and Irons: The Dopamine Management Strategies

If dopamine farming is the day-to-day survival method, then chasing mountains and juggling irons is the long game.

Many neurodivergent folks don’t just manage their dopamine dips with short-term fixes. We build systems around stimulation. Enter the “Many Mountains” and “Many Irons” strategies.

“Many Mountains” is about always having a summit in sight. Finish one big project? Immediately start planning the next. Hit a milestone? Start scouting for another goal to climb toward. There’s a thrill in the chase: the novelty, urgency, sense of progress. Each peak gives us a fresh burst of dopamine.

But it’s not really about reaching the top. It’s about the movement. Because stillness, for many of us, feels like sinking.

“Many Irons,” on the other hand, looks like having ten tasks in progress at any given time. You bounce between projects, rarely finishing one before another lights up your brain. Each switch keeps your mental energy flowing just enough to avoid the dreaded crash.

For a while, these strategies work. They make us productive, engaged, even creatively prolific. We might even feel proud of our momentum. But they’re also exhausting.

Climbing endless mountains can leave you burnt out before you realize it. Juggling too many irons can lead to overwhelm, paralysis, or deep emotional fatigue. Yet, when we stop, we’re faced with that old dread: the crash, the emptiness, the Inventory. So we keep moving.

There’s no shame in using these strategies. They’re ingenious, in their own way. But they’re not sustainable alone. The trick is to notice when the drive to do becomes a desperate attempt to avoid feeling. That’s when it might be time to shift from chasing peaks to cultivating balance.

When Work Becomes the Only Dopamine Source

Let’s talk about one of the most socially sanctioned—and most invisible—forms of dopamine farming: workaholism.

For many neurodivergent people, work can become our identity. It’s the one place where structure, praise, urgency, and clear goals collide to create a steady dopamine drip. And in a world where rest feels threatening and downtime feels dangerous, work becomes a lifeline.

But it’s a lifeline that’s wrapped in chains.

You start checking emails in bed. Skipping meals to finish “just one more thing.” You tell yourself you’ll rest after this project, and then immediately start the next one. You say yes to every opportunity, not because you want to, but because you’re afraid of what will surface in the silence if you say no.

And the world around you rewards it. Promotions, praise, validation—they reinforce the cycle. People call you driven, disciplined, passionate. But underneath the accolades, you’re running scared.

For many of us, workaholism isn’t ambition. It’s protection. From stillness. From shame. From the Inventory. From the crash.

It’s even trickier when you’ve tied your self-worth to what you produce. If you’ve spent a lifetime being praised for performance rather than presence, it can feel like your only value is in your output. So the idea of stopping—even for a day—feels like risking your entire identity.

But you are not your productivity. You are not only as good as your last deliverable.

Managing this behavior doesn’t always necessitate quitting your job or abandoning your passions. Sometimes, it’s about diversifying your dopamine sources.

The Crash: Not a Mood, a Pattern

The crash involves a full-body, full-brain shutdown that can leave you feeling hollow, heavy, or like someone pulled the plug on your internal power source.

You might suddenly find everyday tasks insurmountable. Dishes, emails, even getting dressed can feel like climbing a mountain in fog. Your energy disappears without warning. Things you usually enjoy feel distant, lifeless. You might lie in bed for hours, not sleeping, just stuck. Maybe you scroll endlessly or start a show, only to abandon it minutes later. Nothing satisfies.

And then, as if on cue, the self-criticism kicks in: You’re lazy. You’re failing. You’re wasting your life. You start to panic.

This is the dopamine crash. I have described it as a neurological rubber band effect: your brain, after being stretched to its limit with constant stimulation, snapping back into depletion.

For many, this happens on weekends. You’ve over-functioned all week, masking distress, pushing through executive dysfunction, sprinting on fumes. And when the structure disappears? So does your ability to function.

I call it the “post-work plunge.” You spend the week sprinting through treacle, doing everything you can to keep up. Then Saturday hits… and you drop. You hit a wall. The quiet becomes a void, and the void becomes unbearable.

In response, you might instinctively self-medicate with dopamine sources, like junk food, social media, and retail therapy. But instead of feeling better, you often feel worse. Because what your brain needs is recovery, and not more stimulation.

And yet, the worst part might not be the crash itself, but what you tell yourself about the crash. That it means something’s wrong with you. That you’re broken. That everyone else is managing life better.

But this is a pattern—a neurological, predictable pattern. And if you can name it, you can start to break the shame that feeds it.

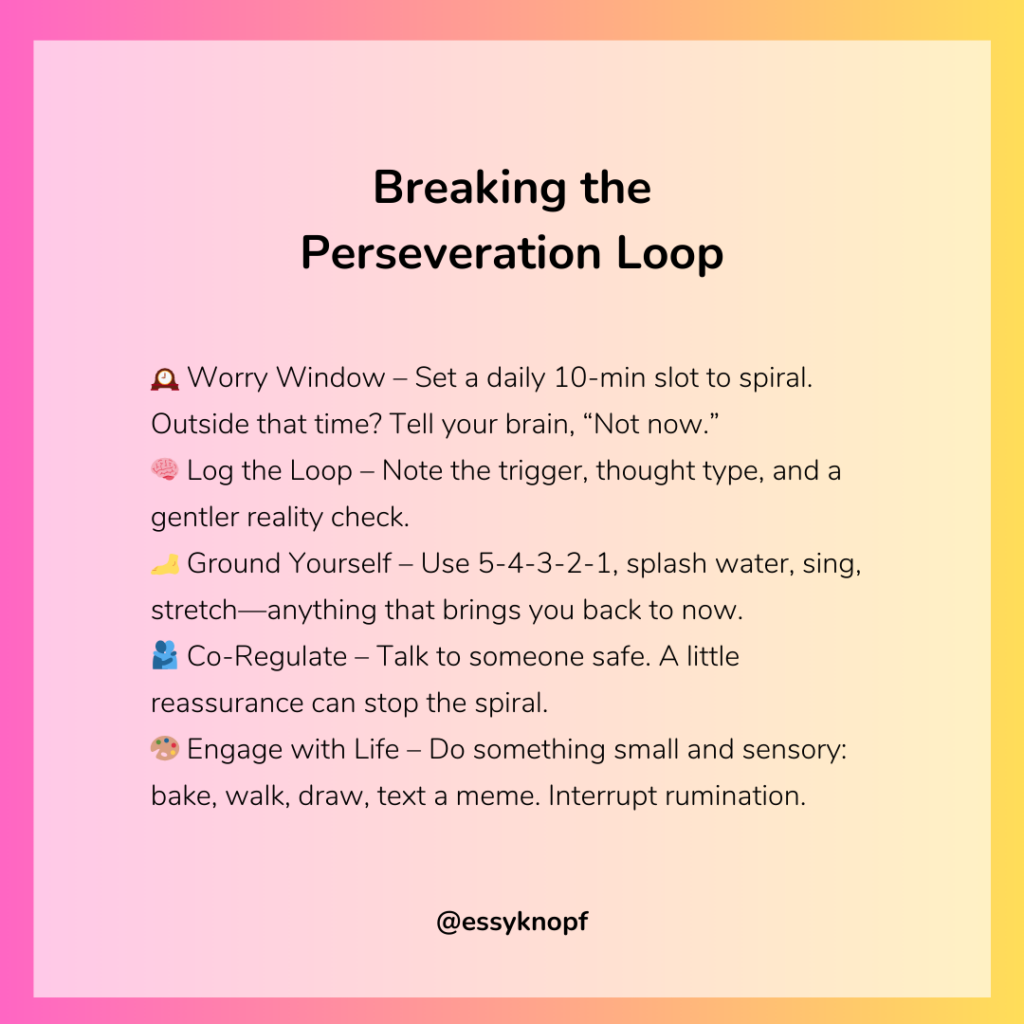

Perseveration: When the Brain Won’t Let Go

If dopamine crashes set the stage for emotional spirals, perseveration is what keeps you stuck in the loop.

Perseveration is that sticky, relentless mental looping where your brain grabs onto a thought and won’t let go. Like chewing on the same worry again and again, even when you know it’s hurting you. Even when you desperately want to stop.

Maybe it’s a fear: What if I never get my life together? Maybe it’s a regret: I shouldn’t have said that. I ruined everything. Maybe it’s a judgment: I’m a failure.

You might know rationally that it’s just a thought. But in that moment, it feels like truth. It feels urgent. Like your brain is trying to solve something, except it’s a puzzle with no solution. Just an infinite loop.

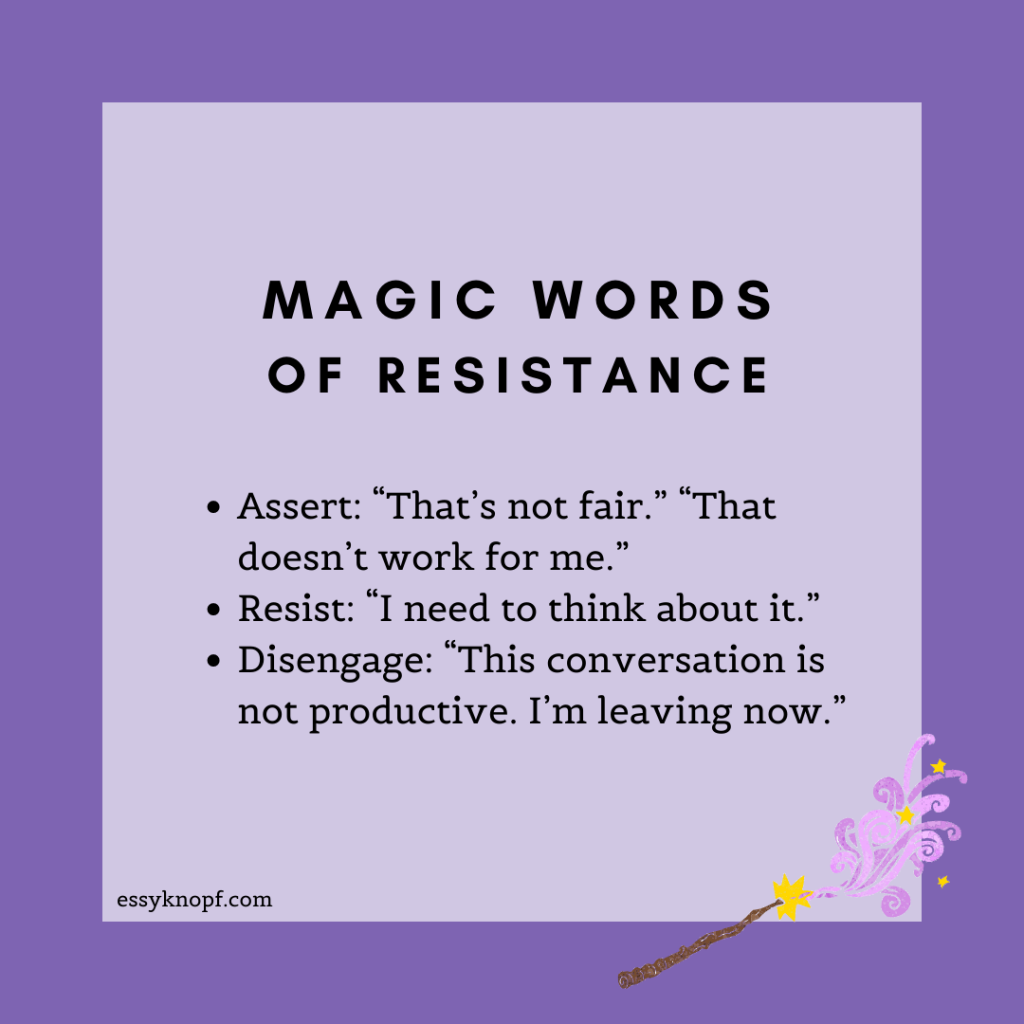

Perseveration is especially brutal during a crash, because your cognitive defenses are already down. Your dopamine is depleted, your executive function is compromised, and your emotional regulation is offline. So when your brain reaches for something to make sense of the discomfort, it often grabs the worst possible narrative, and hits replay.

It’s also deeply physical. Your stomach might tighten. Your chest may ache. Your thoughts blur into background static, except for that one thought, sharp and loud and impossible to shake.

Trying to fight it often makes it worse. Trying to logic your way out? Exhausting.

Perseveration is a symptom of neurodivergence, and often of a nervous system in distress. Of a brain trying to regulate without the chemicals it needs.

So What Helps?

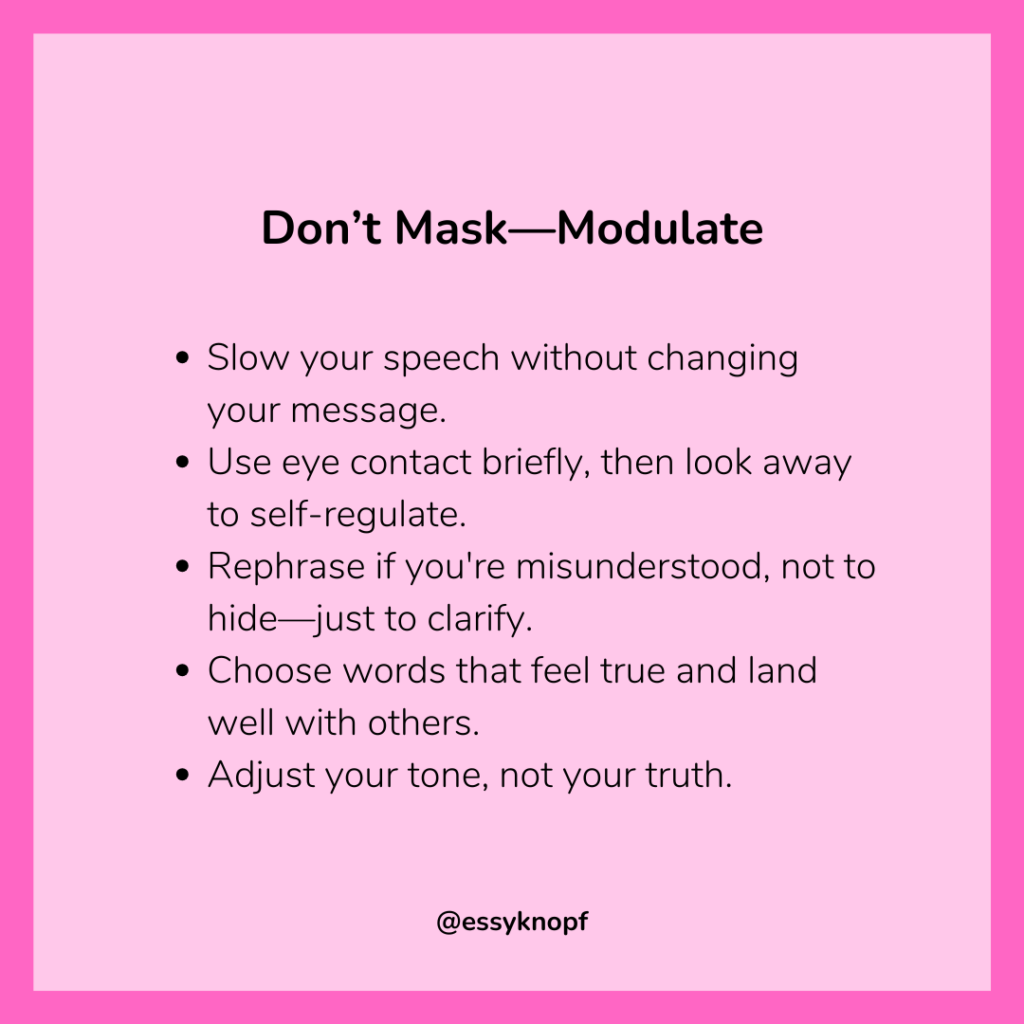

If you’ve seen yourself in these patterns—dopamine crashes, endless inventories, work spirals, perseveration—I want you to know this: you’re navigating a complex, beautiful, and often misunderstood brain in a world that rarely supports how it functions.

This isn’t about trying harder. It’s about trying differently. Supporting your nervous system instead of shaming it. Creating structures that prevent the crash, or soften the fall.

Here are some strategies that can help:

1. Recognize the Pattern

Begin by noticing when the crash tends to hit. Is it after a long week? After finishing a big project? On slow Sunday mornings? Write it down. Track it. See if you can spot the rhythm. This awareness doesn’t stop the crash—but it gives you a foothold in it. It reminds you: This is a cycle. It’s not permanent.

2. Reframe the Narrative

When the Inventory starts, try to pause. Remind yourself: These thoughts might be a chemical response, not an existential crisis. You’re not forbidden from having needs or growth edges. But maybe this isn’t the best moment to decide your life needs a total overhaul. Let your brain recover before trying to interpret what it’s telling you.

3. Schedule Balanced Downtime

Free time doesn’t have to mean empty time. Try building a soft structure into your rest: a planned phone call, a favorite café, a slow walk with music. Include some low-key novelty. I like to mix things, such as video games for engagement, and a casual hangout for connection. It’s like scaffolding for your nervous system.

4. Set Limits on Work

Especially if work is your main dopamine source, boundaries are essential. Start small: no work emails after 7 PM. No “just checking” something on weekends. This boundary will feel uncomfortable at first. You’ll feel the pull to check, to do, to prove. But over time, your system will learn: I can rest and still be okay.

5. Use the “Many Mountains / Many Irons” Strategically

Not all multi-tasking is bad. Not all ambition is avoidance. The key is intention. Ask yourself: Which mountains energize me? Which irons actually nourish me? Are you building something meaningful, or just trying to outrun the crash?

6. Consider Medical Support

For some people, stimulant medication (under medical supervision) can significantly reduce the intensity of dopamine crashes. If this resonates, speak with a neurodivergent-aware psychiatrist. The goal isn’t to “fix” you. It’s to support your brain in functioning with more ease.

7. Mindfulness & Self-Compassion

Practices like journaling, movement, or breathwork can help you stay present and interrupt loops. But more than anything: be kind to yourself. When you crash, don’t ask, What’s wrong with me? Try asking, What does my nervous system need right now?

Sometimes the answer is stimulation. Sometimes it’s stillness. Sometimes, it’s just softness.

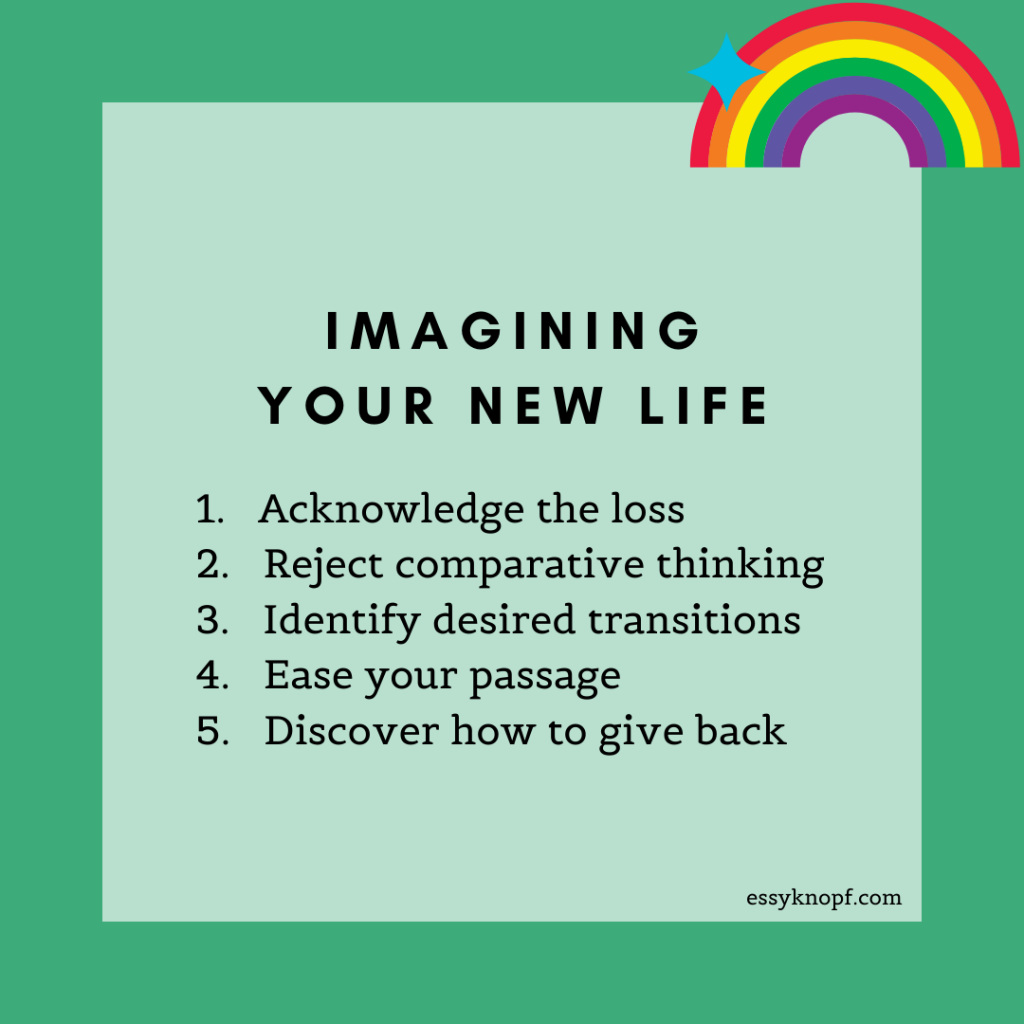

Final Thoughts: There’s a Name for This

If you’ve ever found yourself spiraling the moment life slows down—if rest feels more like a breakdown than a break—you’re not imagining it. You’re likely experiencing the very real, very misunderstood phenomenon of dopamine dysregulation.

This isn’t a personal failing. It’s not a sign that you’re too sensitive, too dramatic, or too lazy. It’s a reflection of how your brain is wired, and how hard it’s working to keep you upright in a world that doesn’t always meet your needs.

When we understand this, something powerful happens: we stop blaming ourselves. We start noticing patterns. And from there, we can create rhythms that honor our neurotype, where stimulation doesn’t have to lead to burnout, and rest doesn’t have to lead to collapse.

This is the work of self-understanding. Not pushing through, but tuning in. Building a life where you don’t need to chase productivity to feel okay. Where rest is allowed. Where balance is possible, even if it looks different for you than it does for others.

You don’t have to live at the mercy of the crash. You can learn to soften it. To ride it out. To meet it with compassion, instead of panic.

What does your crash look like? How do you notice it starting—and what helps you navigate it?

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.