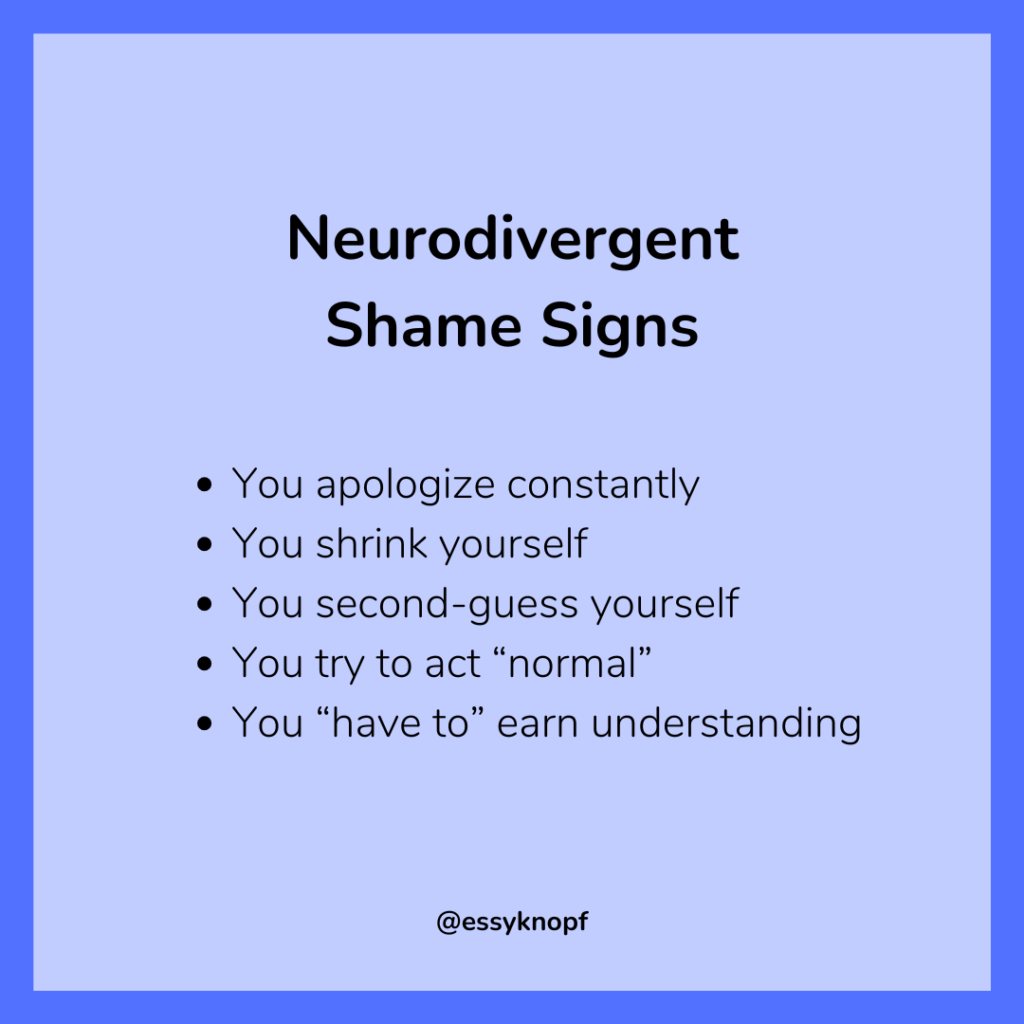

When neurodivergent people-pleasing is a trauma response

There’s a tension I carry in my body, like a coiled spring.

It shows up in the way I brace before I speak. The way I rehearse sentences in my head before I open my mouth. The way I watch for micro-reactions: a raised brow, a stifled sigh, a slight pause in someone’s tone.

This is a learned posture of hypervigilance. A physical manifestation of years spent in what I now recognize as neurodivergent people-pleasing mode.

This behavior becomes our default when we’ve learned—early, often, and painfully—that our natural ways of being tend to invite misunderstanding, correction, or outright rejection. And even when those things aren’t happening in the moment, our bodies don’t forget.

The world may not be attacking us, but we’re still braced for the blow.

For many autistic and ADHD folks, this is the result of trauma; a deep-seated nervous system adaptation to a society that consistently sends the message: “You’re doing it wrong.”

Today, I want to talk about that: what it’s like to live in a constant state of neurodivergent people-pleasing, how it shapes our social lives, and what healing might begin to look like.

The Hidden Trauma Behind Neurodivergent People-Pleasing

When we talk about trauma, most people think of a singular, catastrophic event: a car crash, a violent assault, a natural disaster. But for many autistic and ADHD folks, trauma doesn’t arrive in one big wave. It’s a steady accumulation.

This is complex trauma. The kind that builds slowly, invisibly, over years of being misread, dismissed, or shamed for being different. It’s the slow drip of social rejection. The chronic sense of not belonging. The pain of having your true self constantly questioned, corrected, or ignored.

It’s being the child who was “too sensitive,” “too blunt,” “too loud,” “too weird.” The teen who masked so well they disappeared. The adult who performs normalcy so convincingly that their pain goes unseen.

These experiences don’t just hurt in the moment. They rewire your nervous system. Over time, your brain begins to anticipate judgment. You learn to preemptively scan every room, every face, every word. You rehearse. You shrink. You hide. You brace.

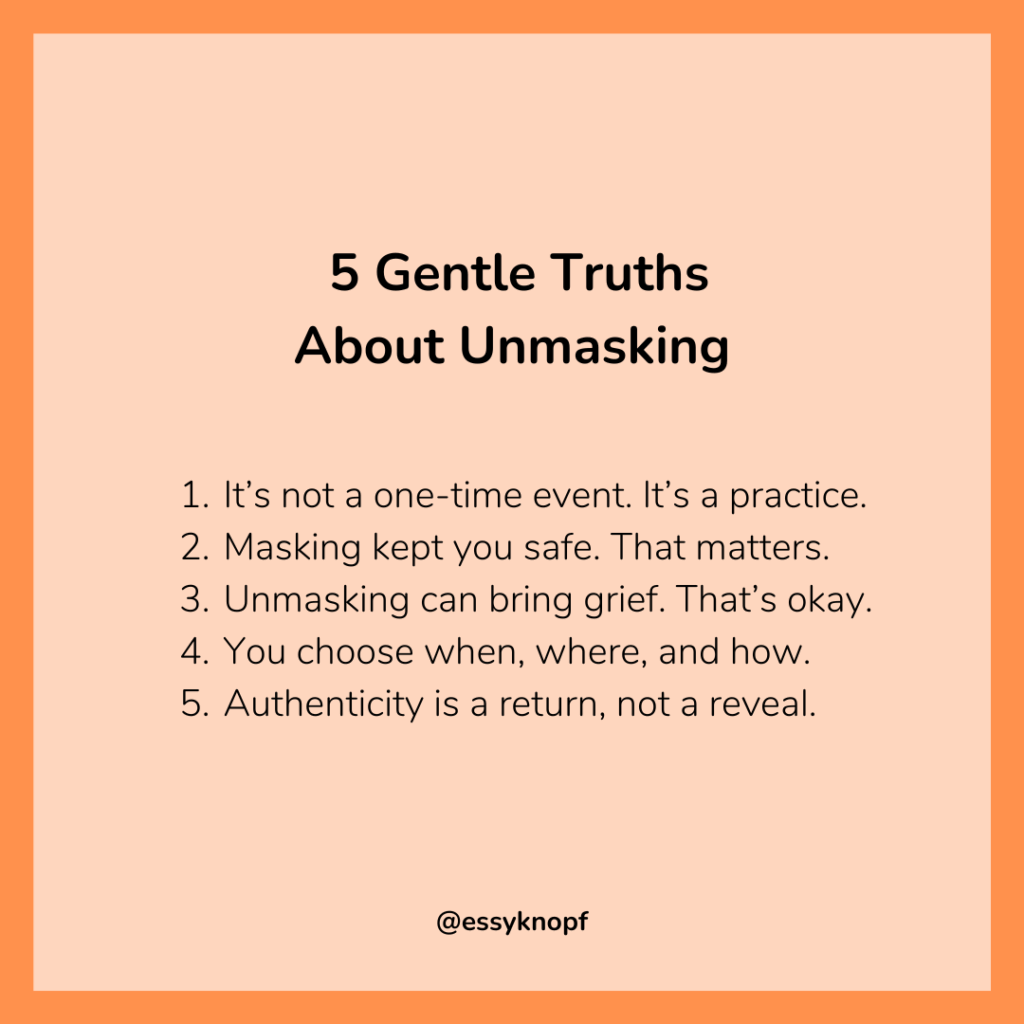

And the most insidious part? Much of what causes this trauma is praised by others.

Like staying quiet in class. Like forcing eye contact while your whole body screamed “no.” Like over-apologizing, over-explaining, over-functioning, just to prove you deserve to take up space.

This is the essence of neurodivergent people-pleasing: performing social acceptability at the expense of your own regulation. Adapting so thoroughly that others never see your distress. Being rewarded for suppressing yourself so effectively that you forget what authentic expression even feels like.

These survival strategies are reflexes, shaped by a thousand tiny lessons: that your comfort makes others uncomfortable, that your truth is too much, that your presence needs softening, shrinking, smoothing over.

But just because it’s common doesn’t mean it’s harmless. Neurodivergent people-pleasing often leads to chronic burnout, disconnection, and shame. Because when you’re constantly performing safety for others, there’s no room to experience it for yourself.

Empathy in People-Pleasing Mode Doesn’t Always Look How You Expect

When you’ve been punished for reacting the “wrong” way too many times, your brain learns to pause. To scan. To script. One of the ways we overcompensate in neurodivergent people-pleasing is by performing a pantomime of empathy.

In many situations that call for it, we may find that our brain is still buffering. Our nervous system might be flooded. Our emotional access might be delayed. Or we may not even know what we’re feeling, because alexithymia and overwhelm can block the emotional signals entirely.

So instead of feeling it in real-time, we run a mental checklist: What would comfort me if I were them? What tone feels safe? What’s the right facial expression to make them feel heard?

What you see on the outside might look like empathy. And in a way, it is. It’s intentional. It’s effortful. It’s us overfunctioning so we can show up, even if we’re still catching up inside.

We’ve learned to perform empathy in a way others recognize. And when we do it well, it usually lands. But it doesn’t feel authentic. It feels like a mask. A role we’ve rehearsed so often that we can do it on autopilot, but never without cost.

And when we’re the one in pain? When we drop the mask and don’t receive that same attunement in return? It stings. It affirms that we must keep performing to stay safe. That neurodivergent people-pleasing is not optional… it’s required.

Flat Doesn’t Mean Unfeeling: The Protective Stillness of People-Pleasing

Sometimes in conversation, we go quiet. Our voice flattens. Our face stops moving. Our answers shrink to short, clipped replies.

To someone on the outside, it might look like we’re annoyed, shut down, or checked out.

But what’s really happening is this: we’re trying to keep ourselves safe.

When you live in the cycle of neurodivergent people-pleasing, your nervous system is constantly monitoring for overload—social, emotional, sensory. And when it gets to be too much, your body does what it needs to do to stay regulated: it goes still.

We adopt a “bratty resting face,” which is often just a freeze response.

It can be triggered by a variety of factors: bright lights and too much background noise; a conversation that’s moving too fast to track; the fear of saying the wrong thing; the emotional weight of alexithymia (feeling something big but having no name for it).

We freeze also because moving might make things worse. We shrink our expressions to minimize risk. We quiet our tone, monitor our posture, try to reduce any variables that might be misread.

Ironically, it’s that effort to appear neutral that often gets misread the most. People ask, “Are you okay?” with a tone that suggests we’re not. They say, “You seem mad,” when we’re doing our best to hold it together. We may have even been told, “You looked like you hated me,” when we were actually doing everything in our power not to melt down in front of someone.

When we mask our overwhelm, we often still get it wrong. Because even silence can be judged. Even neutrality can be seen as hostility.

And so the cycle reinforces itself. We learn that even our coping strategies are risky. That even self-protection makes us vulnerable.

That’s the exhausting paradox of neurodivergent people-pleasing: you’re constantly adapting to avoid being misunderstood, only to be misunderstood anyway.

Hypervigilance As a People-Pleasing Strategy

“Did I say too much?” “Was that the wrong tone?” “Are they mad at me?” “Should I apologize, just in case?”

If these thoughts run on a loop in your mind after even the most casual social interaction, you’re not alone. And you’re not overthinking.

Most of us didn’t wake up one day with this hyper-awareness. We learned it.

We were the kids who asked blunt questions and got scolded for being rude. The teens who didn’t pick up on sarcasm or subtle cues, and got laughed at or excluded. The adults who are still told we’re “too much,” “too direct,” “too intense,” or “too sensitive.”

So we began to monitor ourselves. Every word. Every gesture. Every pause.

We rehearse conversations before they happen. We translate our natural language into something “acceptable.” We apologize for things that haven’t even gone wrong. This is how neurodivergent people-pleasing operates: as a finely-tuned, hypervigilant attempt to stay safe.

And when rejection still comes? We internalize it. It must be us. We’re broken. Dangerous. Too much.

When Intentions Are Misread, the Shame Stays

If you’re autistic or ADHD, chances are you’ve had this moment: you say something you think is helpful. Or curious. Or neutral. And suddenly someone pulls away. Their expression changes. The air in the room shifts.

And you’re left frozen with one burning question: “What did I do wrong?”

It’s a deeply familiar pain. One that activates every learned instinct of neurodivergent people-pleasing. We scramble to clarify, explain, backpedal, soothe.

But often, our attempts to clarify are seen as making it worse. We get told we’re being defensive. That we’re “making excuses.” That we’re “overreacting.”

When all we’re doing is reacting exactly the way someone would if they’ve been through this a thousand times before.

So now, when something feels off in a social moment, we panic. We rush to fix it. We over-explain. It might seem like we’re trying to deflect blame, when we’re really trying to preserve connection.

Because one misstep can feel like the end of a relationship. And often, it is.

What follows is a shame spiral: replaying the conversation on loop, analyzing every word, every glance, and wondering how we got it so wrong—again. And over time, that spiral deepens.

This is the long shadow of neurodivergent people-pleasing. Even when our intentions are good, even when our hearts are in the right place, our words might still be misunderstood. And the pain of that is cumulative.

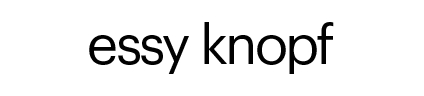

From People-Pleasing to Safety: Reclaiming What Was Stolen

When you’ve spent years in neurodivergent people-pleasing mode, bracing for every social blow, scanning for signs you’ve messed up, scripting your every move, it’s easy to forget what safety even feels like.

Even calm moments can feel like ticking clocks. Even kind people can feel like question marks. Your body doesn’t know how to let go; only how to prepare.

Healing starts not in huge life changes, but in tiny moments. Like when you stim freely and no one makes it weird; you go monotone and no one assumes you’re mad; you say something awkward, and someone laughs with you, not at you; you freeze, and instead of demanding an explanation, someone gives you time.

These are the cracks in the armor. The beginnings of trust. Sometimes it starts with others. But more often, it has to start with you.

With choosing self-compassion instead of shame. With letting yourself pause without apologizing. With reminding yourself: “I’m not too much. I’m not defective. I’m just wired differently. And I’m doing the best I can.”

All of us deserve relationships where we don’t have to constantly manage risk. Where our differences aren’t liabilities, but part of how we exist in the world.

Yes, there will still be people who misunderstand. But there will also be people who don’t need you to perform for their comfort. Who see your flat voice, your delayed response, your stims, your blunt honesty—and lean in.

Final Thoughts

If socializing has always felt like a tightrope walk, you’re not alone.

You’ve just spent too long in neurodivergent people-pleasing mode, a state your nervous system learned to keep you safe in a world that didn’t always feel safe for people like you. And the fact that you’re still here, still trying, still reaching for connection? That’s resilience.

You don’t need to keep proving your worth through performance. You deserve connection that doesn’t demand translation. You deserve to exhale.

Have you found yourself stuck in neurodivergent people-pleasing too? What helped you start to feel safe again?

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.