The trauma beneath neurodivergent moral perfectionism

If you’ve ever felt like you had to be flawless just to be okay—like one slip-up might unravel your relationships, reputation, or even your sense of self—you’re not imagining things. For many neurodivergent folks, perfection is a question of safety.

This pressure to be “good” or “right” all the time is a trauma response; one that often stems from being judged, corrected, or punished for simply being different. This is the root of what we call moral perfectionism.

And here’s the thing: it makes sense. If your lived experience has taught you that being misunderstood can lead to shame, rejection, or even danger, of course you’ll try to control the narrative.

How Moral Perfectionism Develops

For many autistics and ADHDers, moral perfectionism is a slow build, shaped by years of subtle and not-so-subtle messages that being ourselves isn’t acceptable.

Think back to childhood. Maybe you were the kid who blurted out answers, who asked too many questions, who got fixated on fairness or honesty. And maybe the response from adults and peers wasn’t understanding, but annoyance, discipline, or dismissal.

Even when we weren’t explicitly punished, we were often corrected in ways that left deep impressions. A teacher might’ve snapped at you for interrupting when your ADHD brain just moved faster than the class. A friend might’ve gone quiet after you said something blunt, and no one ever explained why it upset them. These moments send a message: You’re not doing this right. Be careful. Don’t stand out.

So we start building rules in our heads. If I just follow this invisible script—if I’m polite, agreeable, emotionally controlled—maybe I won’t get hurt again. This is our attempt to construct a fragile kind of social safety net where the cost of error feels unbearably high.

That’s moral perfectionism: the desperate attempt to avoid harm by being unassailably “good.” It’s armor. But armor is heavy. And over time, it starts to suffocate the very person it was meant to protect.

The All-or-Nothing Trap

One of the most exhausting parts of moral perfectionism is the mental rigidity it breeds—what therapists often call black-and-white thinking or all-or-nothing thinking. It’s the belief that things are either right or wrong, safe or unsafe, good or bad, with no in-between.

This kind of thinking happens because ambiguity feels threatening. If you’ve spent your life trying to dodge social landmines, trying to avoid being shamed for things you didn’t even realize were “wrong,” then certainty becomes a lifeline. It’s easier to think in absolutes when the grey areas have historically been where you got hurt.

So we simplify. We tell ourselves: “If I get this right, I’m safe. If I mess up, I’m in danger.” But here’s the catch: the world is grey. Social rules are inconsistent. What’s “okay” in one group might be “rude” in another. And when we use rigid rules to try and manage a fluid world, we’re left feeling anxious, confused, and often ashamed.

The deeper problem is that this kind of black-and-white thinking affects how we see ourselves. A single mistake becomes a moral failure. A disagreement becomes a personal rejection. Suddenly, we’re not just someone who made an error—we’re a bad person.

Moral perfectionism tells us that being anything less than perfect is unacceptable. But living in that mental space is exhausting. And it slowly strips us of the ability to tolerate being human, with all the messiness and imperfection that entails.

The Inner Critic and External Judgment

If you live with moral perfectionism, you probably know the voice I’m about to describe. The one that says, “You should have known better.” “Why did you say that?” “They’re definitely upset with you.” It’s the voice that replays every interaction on a loop, picking apart your words, your tone, your timing.

This voice is relentless, and it doesn’t care about your intentions. To it, being perfect is the bare minimum. And that inner critic? It was built from all those years of being misunderstood, corrected, or excluded for being different.

For autistics and ADHDers, that critic often takes root early, constantly screaming warnings: Don’t mess up again. Don’t draw attention to yourself. Don’t let them see who you really are. Over time, we start to believe it. We mistake it for truth.

And here’s the twist: the longer we live under the tyranny of this critic, the more likely we are to project its judgments onto others. The same rigidity we apply to ourselves—expecting flawlessness, moral clarity, unshakeable rightness—can begin to show up in how we view the world. We might struggle to forgive others’ mistakes, or feel unsafe around those who act with ambiguity or imperfection.

But again, this isn’t because we’re cruel or hyperjudgmental. It’s because we’re wounded. We’ve survived by holding ourselves to impossible standards, and it feels terrifying to lower those standards—for ourselves or anyone else.

That’s the double bind of moral perfectionism: the critic inside keeps us small, and the judgment outside keeps us isolated. Breaking that cycle begins with recognizing the critic for what it is: a scared part of you trying to protect your heart. But it’s doing so with the wrong tools.

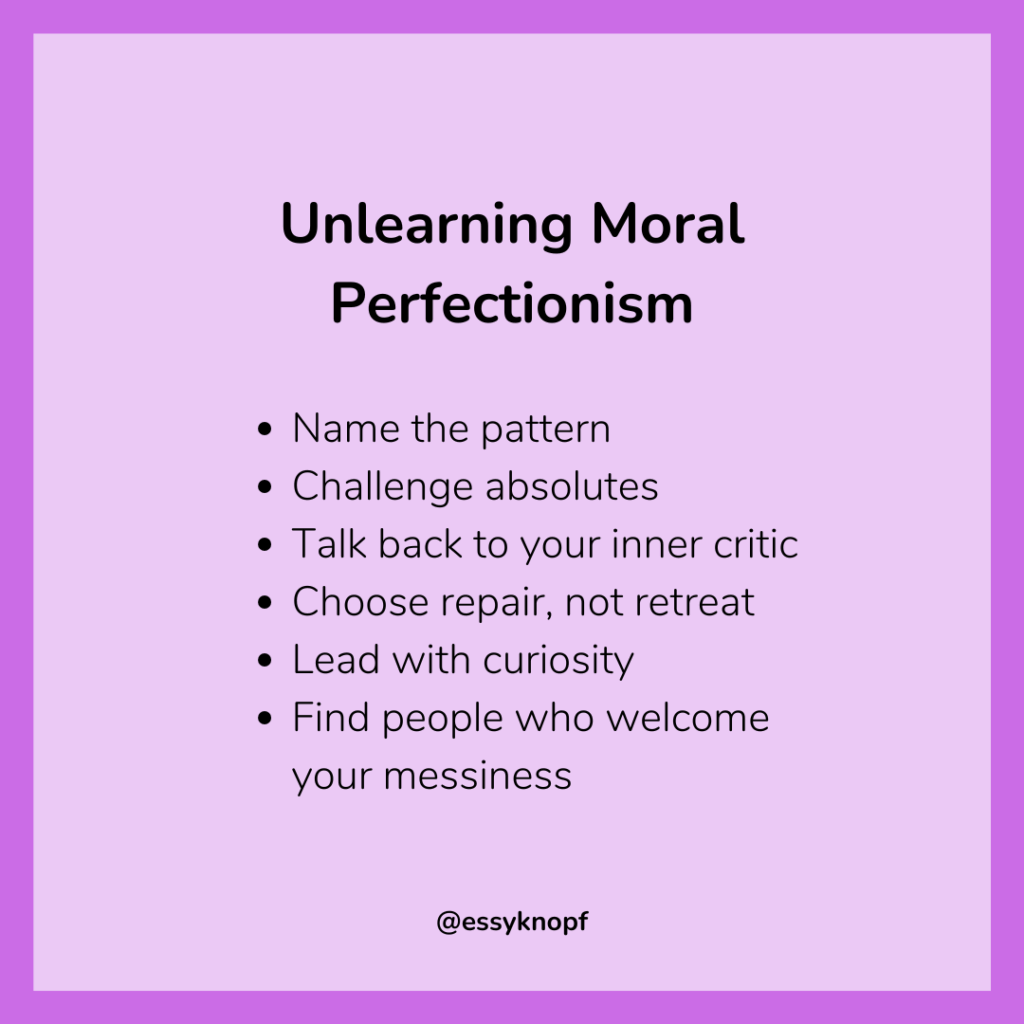

How to Start Unlearning Moral Perfectionism

If you’ve started to recognize moral perfectionism in your life, take a breath. This realization can feel heavy, but it’s also a powerful first step. Recognize that you’ve been responding exactly as anyone might when they’ve had to navigate years of judgment, rejection, and fear.

Unlearning moral perfectionism is about finding safety without needing to be flawless. Here’s how that journey can begin:

1. Name It When It’s Happening

The next time you catch yourself spiraling after a small mistake, pause. Say to yourself, “This feels like moral perfectionism.” That simple act of naming gives you space and turns a reaction into a moment of awareness. And that’s where change begins.

2. Ask: “What Else Might Be True?”

When your brain jumps to catastrophic conclusions—“They must hate me,” “I’m awful,” “This is ruined”—ask yourself: is there another way to see this? Maybe someone’s just distracted. Maybe they misunderstood. Maybe you’re tired. Not every misstep is a moral failure.

3. Recognize the Inner Critic—and Respond Kindly

When that inner voice starts up, acknowledge it: “I hear you. I know you’re trying to keep me safe.” Then add: “But I don’t need punishment. I need compassion.” Picture how you’d respond to a friend in the same situation and try offering that same grace to yourself.

4. Choose Repair Over Rejection

Mistakes happen. Ruptures are part of every relationship, whether personal or professional. When they do, practice staying. You don’t have to vanish in shame or lash out defensively. Apologize if needed, ask for clarification if you’re hurt, and keep showing up.

5. Lean Into Curiosity

Moral perfectionism thrives on certainty. But growth lives in curiosity. Ask yourself: what don’t I know here? What if there’s more to the story? Curiosity softens judgment. It opens space for connection, nuance, and learning.

6. Find People Who Welcome Your Imperfections

You deserve to be in spaces where you don’t have to earn love or acceptance with perfection. Look for people who can sit with complexity, give gentle feedback, and still choose you, especially when you’re messy or confused or unsure.

Final Thoughts

Moral perfectionism is often mistaken for high standards or personal integrity. But underneath, it’s usually something more tender; more painful. It’s the mark of someone who’s been hurt by judgment, by shame, by the endless need to explain themselves in a world that just didn’t get it.

If this post has made you think, “Oh… this is me,” know this: you are not alone. You didn’t choose to live with moral perfectionism, but you can choose to start unlearning it. It takes time and a ton of self-compassion.

You don’t have to be perfect to be good. You don’t have to be morally unimpeachable to deserve love, connection, or support. In fact, it’s in our mistakes, in our honest repair, and in our shared messiness that we often find the truest forms of human connection.

So let this be your reminder: you’re allowed to be complex. To change your mind. To speak imperfectly. You’re allowed to take up space as you are, and not as the flawless version of yourself your trauma once told you you had to be.

Have you noticed moral perfectionism showing up in your own life?

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.