Why ‘eulogy values’ are crucial to our happiness as gay men

For most gay men, the journey from chronic insecurity to enduring wellbeing is fraught. It can be likened to fording a swift river under the cover of darkness, without the benefit of a boat or boatman.

Not only must we fight the currents of the past, but we must also somehow manage to keep our heads above the water in the present.

Without light to guide us, we risk losing sight of the far shore. Without a strong inner resolve, we may surrender and be swept downstream.

Our suffering is often like mud on the river’s banks, so deep and compounded that we risk becoming mired in it before we’ve even reached the water.

In such times, we may be overwhelmed by the temptation to give in to our sense of powerlessness. Accepting that we may have no agency, that change is impossible, leads us to abandon our goals.

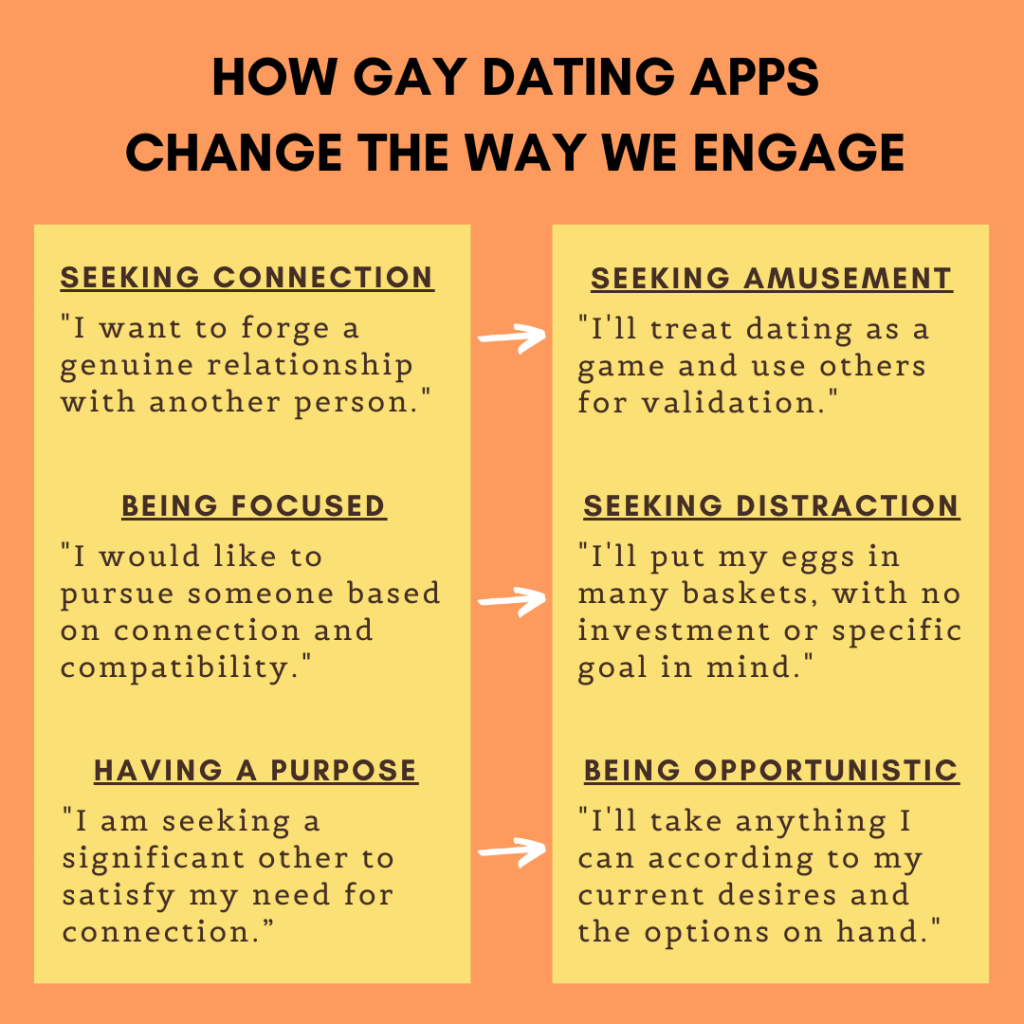

We as gay men often settle for a life of contrary desires and actions, pursuing cheap thrill encounters in favor of purposeful deeds and meaningful connections. But such internal contradictions promise no peace.

Rather, they are likely to only deepen our suffering.

Gay men and impulsive living

When I was in my early 20s and making my first forays into the gay “scene”, I met a man called Jeran.

Jeran was a gentle soul torn by insecurity. Having been abandoned by his father at an early age and bullied at school, he’d moved from the suburbs, seeking shelter in an inner-city gay village.

Despite always being surrounded by other gay men and having a mother who overcompensated to the point of celebrating her son’s birthday with him at a gay club of his choice, Jeran continued to suffer from self-loathing and impulsivity.

I knew Jeran desperately wanted a partner. But rather than attending venues and events geared towards dating, he spent his evenings compulsively cruising hookup sites and nightclubs.

Jeran was more of an acquaintance than a friend, so I was surprised when I received a call from him early one morning some months after our initial meeting.

Thinking it must be an emergency, I answered. Jeran apologized for waking me up then breathlessly launched into an account of his latest hookup.

It quickly became clear to me that Jeran had confused a sexual encounter for a romantic one. When he explained the man he had met had recently split with his wife of some years, leaving his two children in her care, I hesitated.

But for Jeran, the fact the man had admitted this much could only ever be proof of his sincere intentions.

The following day, Jeran called again, seeking my enthusiastic endorsement, while disclosing intimate details that I had no interest in hearing.

By the third call, I finally told him that I needed him to reign it in. To my astonishment, Jeran replied by suggesting I might be jealous and dangled the consolation prize of a threeway

Given I had never expressed sexual interest in Jeran, this left me feeling deeply uncomfortable. I made an excuse and got off the call.

About a week later, my phone buzzed. When I picked up, it was not Jeran this time, but his mother, pleading with me to go and check on him.

Jeran’s suitor, she explained, had stopped returning his calls, and her son was now in hysterics and threatening suicide. Concerned, I went over to Jeran’s studio to talk him through the situation.

A stolid, red-eyed Jeran greeted me at the door. I tried to broach the subject of the breakup, but he deflected.

After a friend arrived to offer support, Jeran—without so much as a word of explanation—opened his laptop and proceeded to watch hardcore porn.

It was as if someone had set the faucet to full blast then switched it off just as suddenly.

Jeran’s denial of the relationship trauma he had just experienced was so complete he refused to take the necessary downtime to process his painful loss and, within a day or so, was back to cruising sex sites.

Over the next few years, I continued to see Jeran online, promoting drug use and branding himself as “semi-masc”—an apparent disavowal of his proud identification as camp.

Part of me wanted to reach out to him. Yet I knew that his entrenched sense of shame would prevent us from ever having the kind of authentic, nurturing conversation I knew he longed for.

Finding your anchor

Jeran’s suffering epitomizes that of many gay men who spend their lives yoyoing between highs and lows, refusing to acknowledge emotions and forever scrambling to find the next fix.

But in becoming preoccupied with the pursuit, we grow ever detached from our core values—values that should serve as a comforting source of stability, whatever the circumstance.

Journalist David Brooks laments this universal challenge in his book The Road to Character:

Years pass and the deepest parts of yourself go unexplored and unstructured. You are busy, but you have a vague anxiety that your life has not achieved its ultimate meaning and significance. You live with an unconscious boredom, not really loving, not really attached to the moral purposes that give life its worth. You lack the internal criteria to make unshakable commitments. You never develop inner constancy, the integrity that can withstand popular disapproval or a serious blow.

Without the grounding influence of a firm value system, those of us suffering the anguish of unsuccessful relationships or the pain of alienation from our authentic identity as gay men may turn to the validation promised by grandiosity, or the quick-fix relief of addictive substances or behaviors.

The problems we face in such circumstances are undoubtedly profound. There are no easy solutions, but if we are to ever find them, we must first be willing to put a moratorium on external distraction.

Only then can we achieve a much-needed internal reckoning.

1. Write a mission statement

Instead of trying to find solace in our ever-changing physical reality, we can turn to the inner world of principles.

By actively engaging with our value system, we generate positive change. To quote Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Sow a thought, reap an action; sow an action, reap a habit; sow a habit, reap a character; sow a character, reap a destiny”.

How do we identify our principles? We can start by asking questions like:

- What’s most important to me?

- What values do I believe in practicing daily?

- What am I most willing to fight for?

- What is my definition of a healthy, content, balanced life?

- What nourishes my body, mind, and spirit?

Look at your answers, making sure to distinguish between what Brooks calls “resumé values” and “eulogy values”.

Resumé values are values concerned exclusively with material success, the kind that sounds great on your resumé.

Eulogy values, on the other hand, are tied to your character. These are the traits loved ones might celebrate at your funeral.

Once you have identified your eulogy values, frame them as statements about how you intend to live your life, and why.

List these principles on a one-page document. Close your statement with a pledge of commitment and sign the bottom.

Congratulations! You now have a mission statement.

Now print out copies of this statement and tape them in places where you’ll be reminded on a daily basis of the code by which you have chosen to live your new life.

2. Set some S.M.A.R.T. goals

S.M.A.R.T. stands for five categories: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. This goal tracking system helps break objectives into easily understood and trackable metrics.

Begin by brainstorming some goals in service of your newly articulated principles. Then download a S.M.A.R.T. goal planning spreadsheet and organize them into the five categories listed above.

For example, if healthy eating is a value you’ve identified, you can consider meal planning each week and preparing some home-cooked meals.

If you’ve listed community service as a goal, you can set aside time to volunteer for some nonprofits in your local community whose services you feel are valuable.

If you’ve decided you want to live a more mindful existence, consider implementing a 15-minute daily meditation practice.

In order to help you stick with your new resolutions, you may want to set reminders on your phone or program a habit-tracking app. Make sure to regularly check back on your progress at the times you’ve designated under the “T” section of your goal planner.

The act of setting these goals alone will affirm your self-worth. And when you follow through with them, you are taking intentional steps towards creating a lifestyle defined not by the desire to escape but to embrace.

3. Be kind to yourself

Our society is addicted to the notion of instant “Cinderella-style” transformations. Transformation, however, runs on its own clock.

For this reason, you must be both patient and kind to yourself. Many gay men have a tendency towards achievement and perfectionism.

If this sounds like you, ensure your goal-setting and fulfillment does not become yet another behavior characterized by compulsivity.

Instead, practice listening to your feelings and needs. Cut yourself slack when needed. Treat this as an opportunity as much for growth as for self-compassion.

Remember that you are tending a garden that will, in time, bear fruit. Conscientiousness and persistence are key.

The alternative is neglect, and we know very well the costs of this: the overgrown patches where snakes lurk, the flowers choked by weeds, the gnarled trees with their spoiled fruit.

Craft a bold vision—one guaranteed to bring wellbeing and security, then carefully cultivate it.

“He who has a why to live,” says German philosopher Nietzsche, “can bear almost any how”.

Takeaways

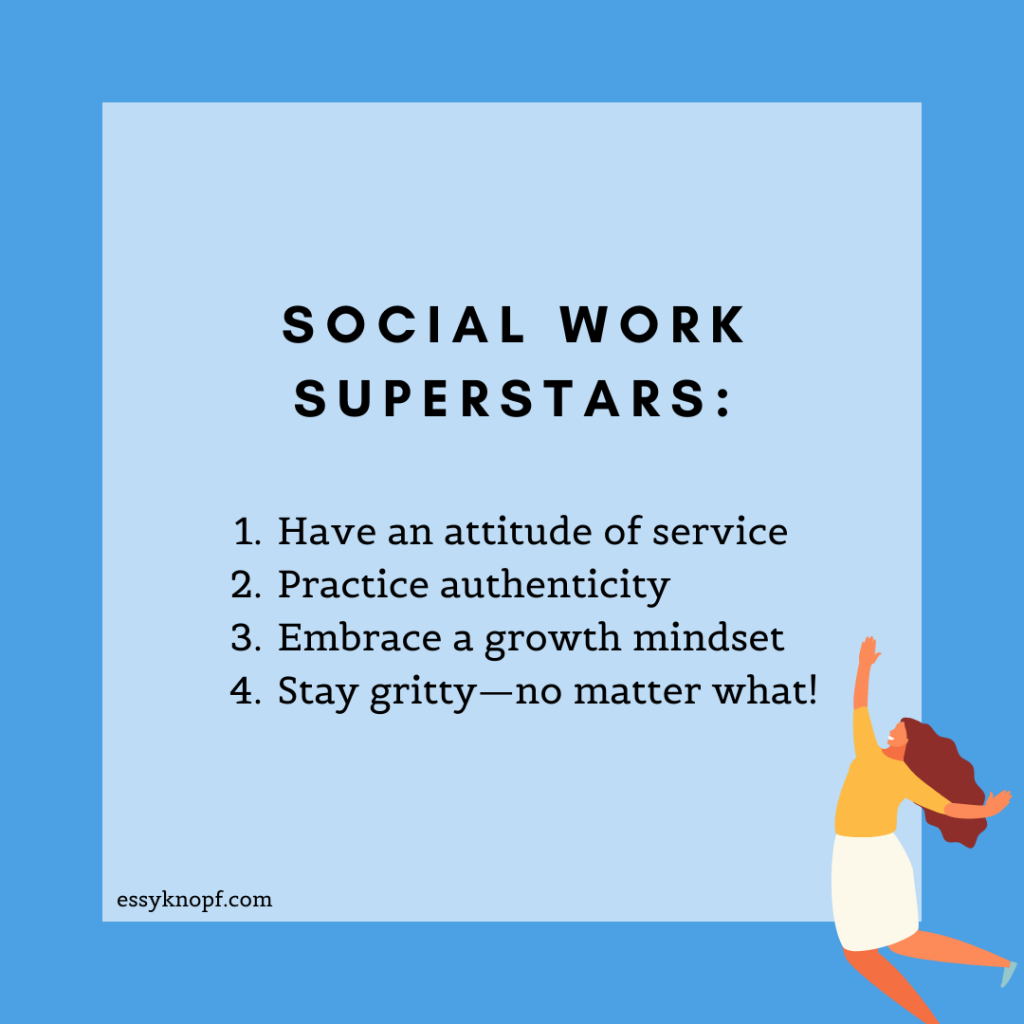

- Write a mission statement identifying the values that are most important to you.

- Set goals in service of these values.

- Break your new goals down into action steps using the S.M.A.R.T. system.

- Pace yourself, and remember to practice self-compassion.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.